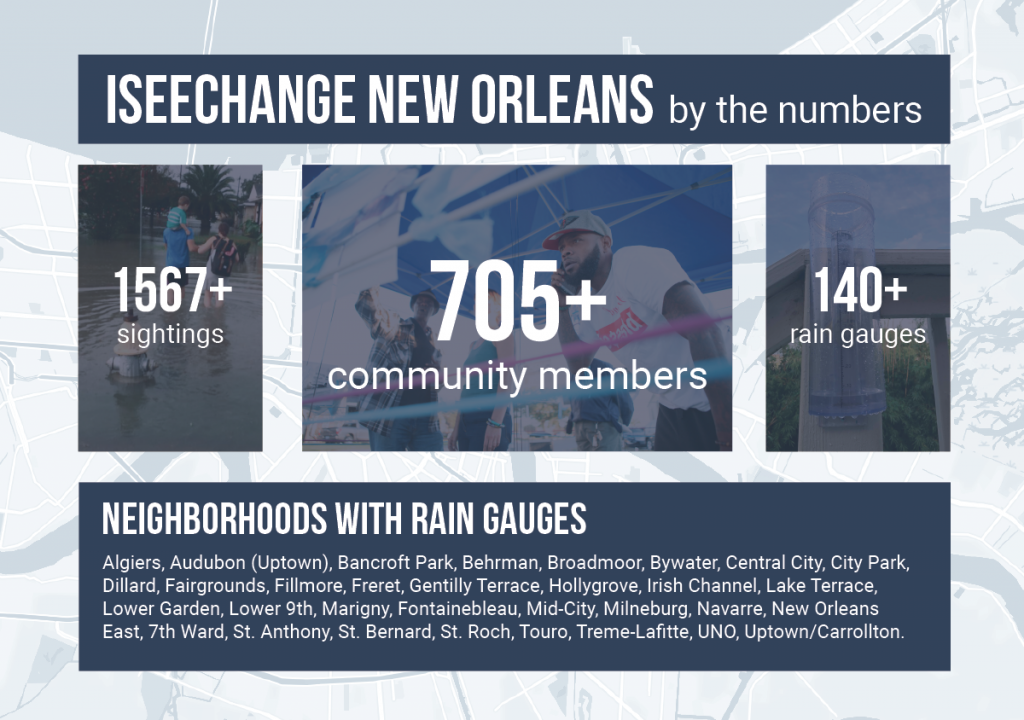

In New Orleans, ISeeChange works to understand storms, flooding and how weather and climate change impact residents’ daily lives. Since its initial pilot in the Gentilly neighborhood in 2017, the ISeeChange community in the city has grown in members, observations and impactful contributions to city knowledge.

In 2018, ISeeChange and NOLA Ready teamed up to create a network of rain gauge hosts across the city. Residents post rain totals to ISeeChange alongside photos of flooding, and stories of storm impacts.

Rain gauges are still available through the end of 2019, for residents looking to learn more about their rainfall– request one through the ISeeChange app or online today!

New Orleans, our hometown community, has provided ISeeChange a testing ground to not only develop data collection and engagement methods, but to also understand how best to provide the city and other decision makers with resident’s detailed expertise of how the weather impacts their neighborhood and daily life.

“The ISeeChange New Orleans community is contributing unique data and stories to monitor, inform, and design local adaptation and infrastructure projects,” said Julia Kumari Drapkin, ISeeChange CEO and New Orleans resident. “It’s also contributing to insights in communities across the country looking to do the same.

What ISeeChange has learned so far in New Orleans

1. The impacts of rain storms in New Orleans are extremely localized.

Storm totals can vary several inches from one neighborhood to the next, as can flooding. During a storm on August 26, 2019, a gauge host in Broadmoor recorded 3.6 inches of rain in the western part of the neighborhood while a host in southern Broadmoor recorded 6.6 inches of rain. On July 10, 2019, a rain gauge in Bancroft Park collected 4.76 inches of rain while a gauge just a few blocks away, at the corner of Harrison and St. Bernard, collected 5.54 inches of rain. Across a distance of a few blocks, the amount of rain decreased by almost an inch, lowering from a 25-yr event to a 10-yr event: which dramatically impacts the degree to which local infrastructure can manage a storm.

2. The more neighbors posting, the better.

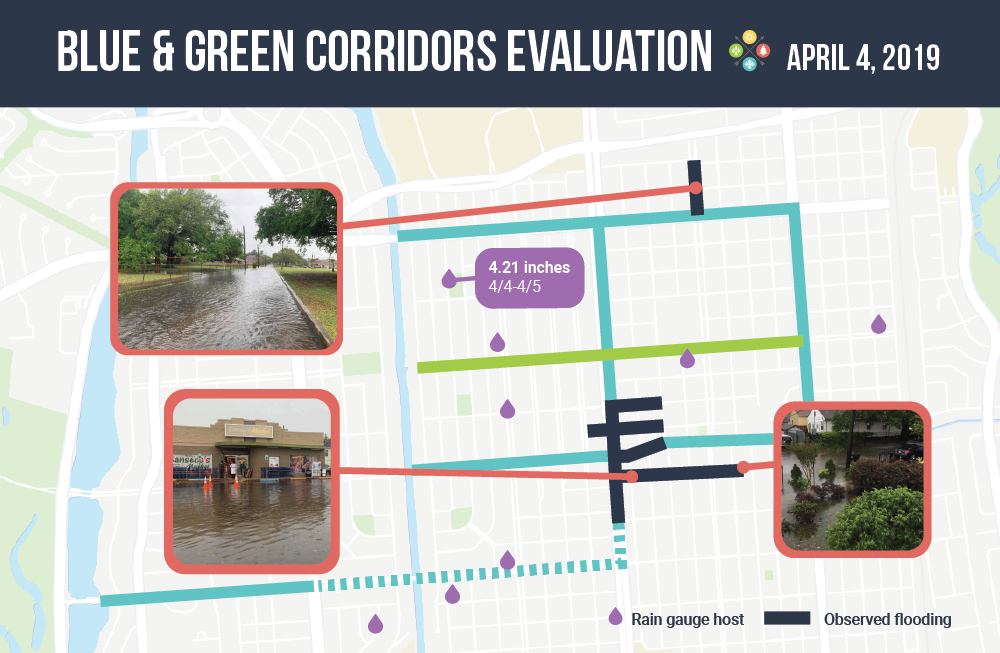

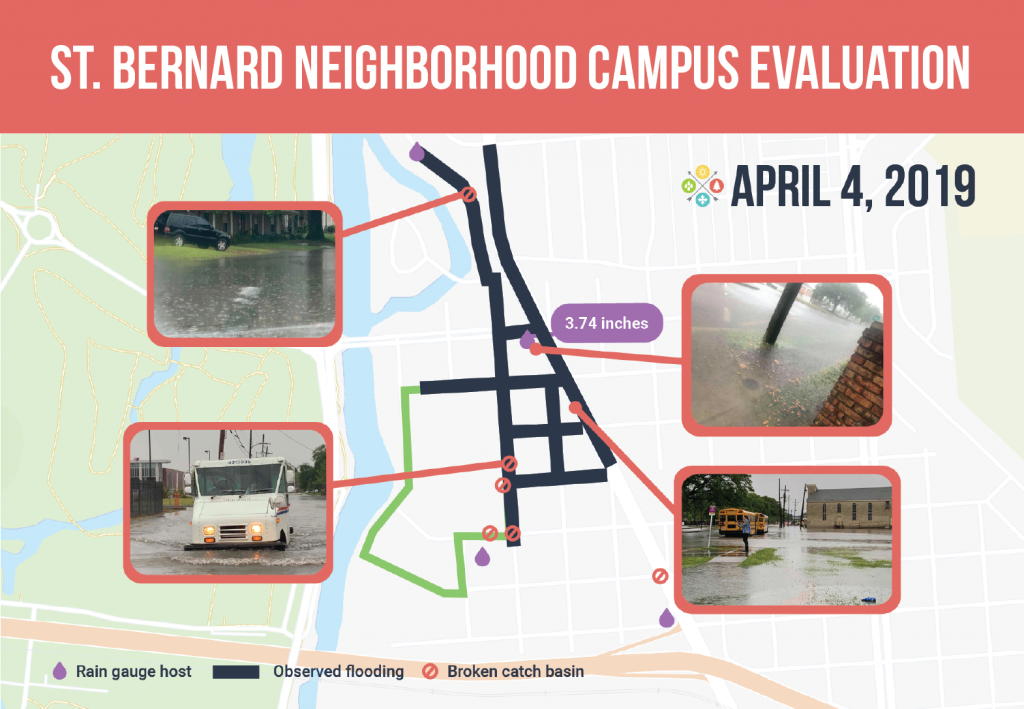

Originally, ISeeChange outreach was focused on recruiting residents in Gentilly. As a result, the record of rain totals and flooding in Gentilly is more advanced than elsewhere in the city. Networks of neighbors there have helped evaluate modeled data where green infrastructure projects are planned. ISeeChange community members have helped inform design on the Blue & Green Corridors and the St. Bernard Neighborhood Campus project areas.

More observations create more data points that offer more opportunities to compare rain totals and flooding impacts across small distances. The more neighbors posting and connecting what they see, the better our understanding of how the topography, built environment, and infrastructure interact to alleviate or worsen flooding.

3. Residents can identify places for potential adaptation infrastructure.

Photos of open spaces or empty lots that regularly flood can alert ISeeChange partners and the City to places that may benefit and be available for stormwater mitigation projects. Take Amy Stelly, in Treme. She not only documented record-setting rains on July 10th -getting some of the highest rain totals in the city and consistent with official measurements – she’s also using ISeeChange to document potential solutions. She thinks Hunter’s Field under the Claiborne overpass can be used to store water and alleviate flooding in the 7th Ward.

More flooding at Hunter’s Field playground. The conditions are exacerbated by runoff from I-10.

4. Drainage details during storm events are helpful.

The most useful drainage data points are the time when flooding starts and the time when it stops. It’s not always easy for residents to know these times, particularly if storms happen overnight or during the day when they may be working. Even if specific times are recorded, notes on when the flood has drained, or documentation of high-water marks like lines of leaves, debris, or soil on the sidewalk. On Chatham street in Gentilly, Water from a precursor to Barry fell until 9:30 a.m., but remained on the street until 12:30 in the afternoon. Pictures of oak leaves pushed by street flooding up on the sidewalk show how close residents came to dealing with flooded cars and ground floors.

Conventional wisdom suggests that, across the whole city’s drainage system, rain events that do not exceed one inch in the first hour and a half-inch every following hour – should not cause flooding. But lately, residents experiences have exceeded that. Storm events this spring and summer, documented by ISeeChangers in New Orleans, showed several storms that dumped several inches of rain in one day.

Generally, the City’s drainage system should be able to manage a “2-year-storm,” or a rain event that has been calculated to have a 50 percent chance of occurring in a given year. In New Orleans, NOAA Atlas 14 defines a 2-year-storm as less than 2.3 inches in an hour. With climate change increasing the probability of intense rain events, these designed storm designations based on historical averages are less accurate. It is increasingly common that storms across the city are exceeding the two-year threshold.

Additionally, the amount of water that the system can handle is difficult to localize– drainage varies based on local topography, location within the drainage network, the variance of rainfall across the surrounding neighborhoods, catch basins and the sizes of pipes that lead to drainage culverts, as well as the infrastructure’s ability to perform with different rain events simultaneously in the same basin.

For example, areas near pump stations can be expected to be among the last places to drain because stormwater from other areas will likely converge there. As a result, there’s not a sense of what a “normal” drainage time looks like for individuals across the city. Residents may be flooded by another neighborhood’s rain. Comparing observations of rain totals and flooding drainage times across multiple rain events is helping us and our community members get a better sense of the extent and timing of flooding different areas may be able to expect.

In the summer of 2017, the ISeeChange team tracked drainage times for every storm event at the corner of Harrison and St. Bernard in Gentilly and learned the corner and northeastern side of the neighborhood is prone to pocket flooding, even after the catch basins have been cleaned or totally rebuilt. Firms contracted to work on city water infrastructure and the city have been informed and attempts have been made to include this area of the neighborhood in green infrastructure plans.

This summer, more than ever before, individual residents submitted their own drainage time data. As residents continue to post similar information during future rain events, comparisons and analysis can be done to study changes and opportunities for infrastructure solutions, especially as the City considers $250 million dollars in stormwater bonds as well as $12 million dollars annually in new millages for drainage improvements and street repairs.

5. Photos can give clues to how high flood waters reach.

In photos posted by residents of flooding, any stationary objects with distinctive markings can provide useful data. For example, in a photo of a sidewalk corner ramp, ISeeChange and our engineering partners can estimate water heights in areas of interest and use that as a data entry input into flood models. Flood height data entry points will soon be added to flood investigations.

6. Information about catch basins and other stormwater infrastructure alongside flood observations provides important context.

Flood posts that note whether a catch basin has been recently cleaned allow us to see that the problem is not with a clogged catch basin but with something else.

Catch basins are placed in the lowest parts of the street where water is funneled and collected. Across the 300-year-old city, there are a variety of types of catch basins, but they all function essentially the same way, said Cheryn Robles with the Department of Public Works. Each catch basin collects water into a brick chamber, the water then flows through a diagonal pipe to a main pipe that runs parallel to the street above.

Folks doing their part, clearing catch basins ahead of Hurricane Barry.

If residents think that there is an issue with their catch basin, the first step is to make sure that any debris in front of the opening is clear. If it is clear, and there still appears to be a backup, residents can look inside the basin to see if they see mud or anything else that could be blocking the flow of water. If there does appear to be mud, Robles said, residents should call 311 and the city will send a vacuum truck to clear it. If drainage problems persist, there is likely an issue with either the smaller diagonal pipe or the main pipe.

“It’s usually that they just need to be cleaned, but there’s a fair amount of locations that have a broken pipe,” Robles said. Repairing these kinds of issues requires the city to dig up the street and can be expensive. Robles said that an initiative to raise funds for pipe repairs is on the November 16 ballot.

7. Residents perspective helps evaluating infrastructure projects

During the rain storm on July 10, 2019, residents in a Southeast Louisiana (SELA) Drainage program project area, which is designed to handle storms with a 10 percent likelihood of occurring each year (a 10-year storm), saw extreme flooding and wondered why the project wasn’t working.

— R Bridge

As recorded by ISeeChangers across the City, and later verified by the City’s commissioned report by Ardurra, the July 10 storm was much more intense than the 10-year design storm. In some areas, the rainfall was more equivalent to a 100-year design storm (which has a one percent likelihood of happening each year). As residents post rain totals in real time, ISeeChange aims to provide ways for residents to evaluate for themselves how severe any one storm is, what kind of flooding to expect, and how best to mitigate it.

In addition to evaluating city stormwater infrastructure, ISeeChange posts can be used to evaluate personal projects and solutions. Individual residents post stories of how their own stormwater management solutions — like rain gardens and french drains — are working.

8. Persistent puddles can identify areas dealing with subsidence, or the gradual sinking of land.

Much of New Orleans is built over paved swampland. As the soils beneath our streets shrink and swell, our streets sink and our pipes break. Those areas tend to fill up with water whenever it rains. Residents can record these areas of their street that regularly have standing water by taking photos and noting how long the puddle lasts after a rain event. These areas are ones that can benefit from rain gardens or local green infrastructure projects and help prevent subsidence by restoring water to the subsurface.

Future work with the ISeeChange community in New Orleans

ISeeChange will continue to work with NOLA Ready to distribute rain gauges and gather rain data. The ISeeChange team has been increasingly involved with connecting community observations to green infrastructure designs in the Gentilly Resilience District and plans to continue to work alongside engineers and decision makers on stormwater projects across the city.ISeeChange is also launching new technology that will allow additional sensor data to be synced with community posts.

Additionally, ISeeChange is rolling out an urban heat project in New Orleans to better understand areas in need of cooling projects (like shade tree plantings) as well as the health impacts of urban heat. Residents can get involved by posting observations and stories of how heat impacts themselves and their neighborhood, as well as changes to trees or other first of season changes like bloom times or allergies. The ISeeChange team will be working with the New Orleans Department of Public Health to deepen our understanding of health impacts and heat in 2020.

There’s no one way to post. New Orleanians can also post any climate and weather related questions they have and the ISeeChange team will work to get them answers.

When you talk, we listen and we look into whatever and whenever you see change.

Cover photo by Bart Everson via Flickr.