In the four years since Jill Shampine moved into New Orleans’ Pilotland, also called the St. Bernard neighborhood, she has experienced five major floods. She began documenting the flooding that she experienced on ISeeChange after a particularly bad storm in 2019 which left her stranded blocks from home until her boyfriend could pick her up in a kayak.

“When it’s storming most people are like, ‘Oh, it’s raining, it’s a cozy day at home, I’m safe,’” Shampine said. “For me, I’m like constantly getting up asking, ‘Where’s the water at? Is it draining? Is it rising? Do I need to think about moving my car to the school lot or the nursing home lot since it’s higher ground?”

Pilotland is a historic, low-lying section of the Gentilly neighborhood that was hit hard by Katrina. Among the area’s losses from the storm were the Willie Hall Playground, the sports fields at McDonogh 35 College Preparatory High School, the first Black public high school in the city.

Jimmie Davis, a business owner in Pilotland, has lived in the neighborhood for nearly 70 years. He remembers playing at the school fields and fishing on Bayou St. John, which is accessible from the neighborhood, with his brother when he was young. During the hurricane, his house was filled with six feet of water for two weeks. Recovery, he said, is ongoing and began even before Katrina.

“I’ve been working on my house ever since Betsy, really,” Davis said. Hurricane Betsy hit the Gulf Coast in 1965.

Now, even small rainstorms cause flooding that impacts his home and business. All of the storms, big and small, add up to make life in Pilotland more complicated. New and long-time residents like Shampine and Davis want to see lasting change. ISeeChange has been helping inform a new stormwater project there that is nearing construction and aims to take some of the pressure of flooding off of the neighborhood.

History of the St. Bernard Neighborhood Campus project

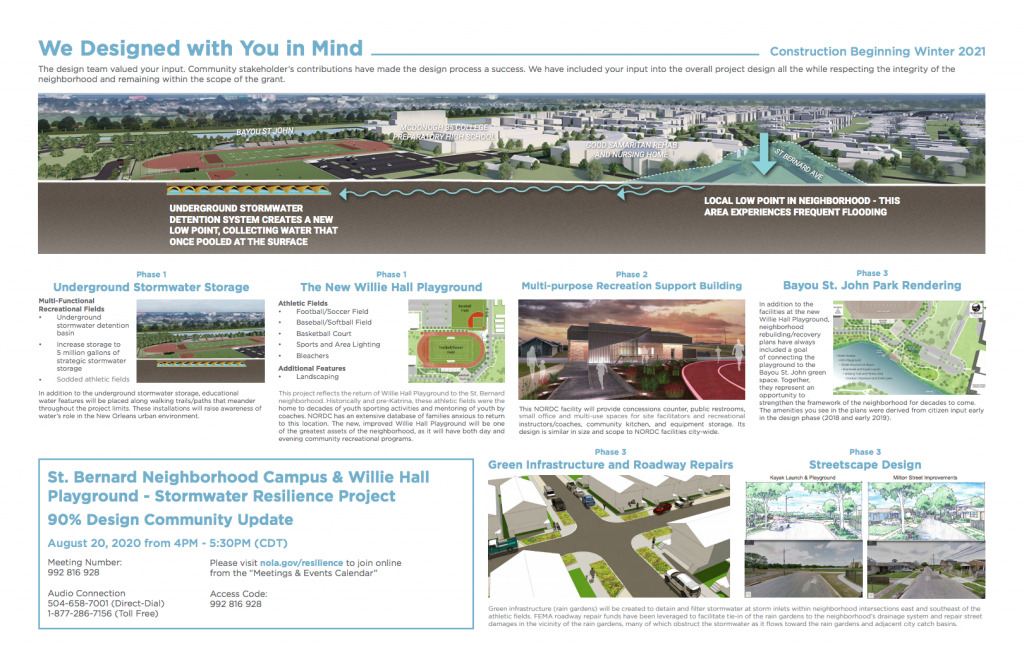

Plans were already in place to redevelop the playground and fields when, in 2016, New Orleans was awarded more than $141 million from HUD’s National Disaster Resilience Competition. With that grant, the Gentilly Resilience District was born. The district’s projects are intended to reduce flood risk and support the community’s continued recovery efforts. The award was granted in part because of existing revitalization projects.

The St. Bernard Neighborhood Campus is helping return what the community lost to Katrina said Larry Barabino, CEO of the New Orleans Recreation Development (NORD) Commission. Barabino grew up playing in the playground along with other kids in the St. Bernard housing project. Not only will neighborhood kids be able to walk to the playground to play again, but the Willie Hall sports teams will return to their original park space.

“They’re waiting to come home,” Barabino said of the teams that have been based in other NORD facilities. “They refused to change their name to be anything other than Willie Hall Playground.”

When complete, the six large-scale urban water projects that make up the Gentilly Resilience District are expected to significantly reduce strain on the drainage system, which will lessen the occurrence of minor flooding and the severity of major floods.

“In the overall Gentilly Resilience District we are providing a lot more stormwater benefits which relieves pressure on the pumping,” said Tom Cancienne, a principal engineer at Stantec which is leading design on the project in Pilotland. That project is called the St. Bernard Neighborhood Campus and the word campus is used as the project originated on the campus of McDonogh 35.

The campus is in its final phases of design, and the project team, led by the City of New Orleans’ Project Delivery Unit for Sustainable Infrastructure, will co-host a virtual community meeting with the design team on August 20 to discuss the 90% design plans, which includes the largest underground stormwater storage chamber in the Gulf region.

How ISeeChangers influenced design

Throughout the design process for the campus, engineers and designers used flood and rain gauge sightings from ISeeChangers like Shampine to understand the block-by-block differences in flooding and flood impacts.

“We saw in the models the area did experience flooding in a general sense, but we were able to pinpoint more precisely which streets were more vulnerable to flooding,” Cancienne said. “Which helped us to try to focus our design and our efforts on those particular streets.”

Since 2016, ISeeChangers have submitted 200 sightings from Pilotland, and documented 28 flood events. Significant flooding was reported on August 5, 2017 (a 10-year-storm), April 5, 2019 (a 2-5-year-storm), May 12, 2019 (a 2-5-year-storm), and July 10, 2019 (a 25-year-storm).

For residents like Shampine, posting about flooding on ISeeChange provided them a way to collect the issues that they were seeing, learn more, and advocate for change. Shampine even reached out to the City to see if they could use part of a lot that she owns for stormwater storage.

“I do think that sometimes certain neighborhoods get more attention,” she said. “I feel like people kind of forget about this neighborhood, so I’m happy to contribute and put us on the map, so everyone can see what’s going on here.”

Project design updates

At 90% complete, the St. Bernard Neighborhood Campus plans include the underground stormwater chamber, a football field, a baseball field, a basketball court, a grandstand and landscaping and lighting for the area.

In the current designs, the stormwater chamber is shaped like an “L” and is intended to store upwards of 4.8 million gallons of water.

During a storm, rain accumulating on the street will go through storm drains and then pipes to reach the chamber. The water will then move from the chamber to Pump Station 3 on north Broad and Florida Avenue. In New Orleans, pumping stations are the biggest choke points in the drainage system because they can only process so much water at a time. The St. Bernard project provides a place for stormwater to be stored off the street level until the pumps have the capacity to push it out of the city. As a result, the amount of time that water floods streets, particularly during the most frequent low- and medium-intensity rain storms, should be reduced in the neighborhood.

“They’ll see more of the benefits in the two- and the five-year storms because we’re kind of limited in terms of what we can do because we all flow to the same pump station,” Cancienne said. “And we have a finite amount of area where we can provide stormwater storage.”

What comes next

Now that the designs for the chamber and fields are almost complete, the project team is holding a virtual meeting on August 20 from 5:30pm – 7:00pm. Residents are encouraged to attend to learn about the project and provide feedback.

ISeeChange has heard from residents that are concerned about project details, gentrification, community access to the field’s concession stand, the limitations of the city’s pumps, and the amount of relief they will get during bigger storm events. This meeting provides a chance to voice those concerns and learn more about the project.

“You want to lay out the basic plans, but the reality of things is more than pretty renderings,” Shampine said. “Those deeper conversations will hopefully be had in this design meeting.”

Once designs are finalized, the project will move into the bidding process for construction, in which companies will be contracted to make the designs come to life. Construction, which will occur in three different phases, is supposed to be completed by 2022 according to current HUD rules. The first phase will be the construction of the chamber and sports fields. The second phase is the construction of a concession stand, bathrooms and office space. And the third phase, which will stewardship from residents, will focus on green infrastructure and recreational spaces for the neighborhood alongside Bayou St. John. This green infrastructure will supplement the stormwater chamber storage by providing natural areas to store and slow stormwater’s movement through the drainage system.

By continuing to collect and share flooding observations throughout the neighborhood on ISeeChange, residents can provide insight into plans for phase three. Additionally, observations about the impacts of heat in the neighborhood are important as the green infrastructure work in phase three can also be designed to provide cooling.

“Trees are good, and it helps us to know where and in what location they’re best to provide shading for the residents,” Cancienne said. “There’s not a whole lot of information out there regarding that, and I think ISeeChange is providing good information for us during the design process.”

ISeeChangers are also sharing observations in some of the other project areas of the Gentilly Resilience District, including in St. Anthony and Milneburg, where the Blue and Green Corridors project is nearing 90% design. Neighbors should stay tuned for project updates and keep posting information that will help document the neighborhood transformation.