Whether there’s snow or not, February brings a blizzard of white to the skies over North Carolina, in the form of snow geese and tundra swans.

#ISeeChanger Keith Maurer noticed these migratory birds leaving his favorite North Carolina wildlife refuge spots earlier this month. “Seems odd for early February. Is this just another result of our very mild winter?”

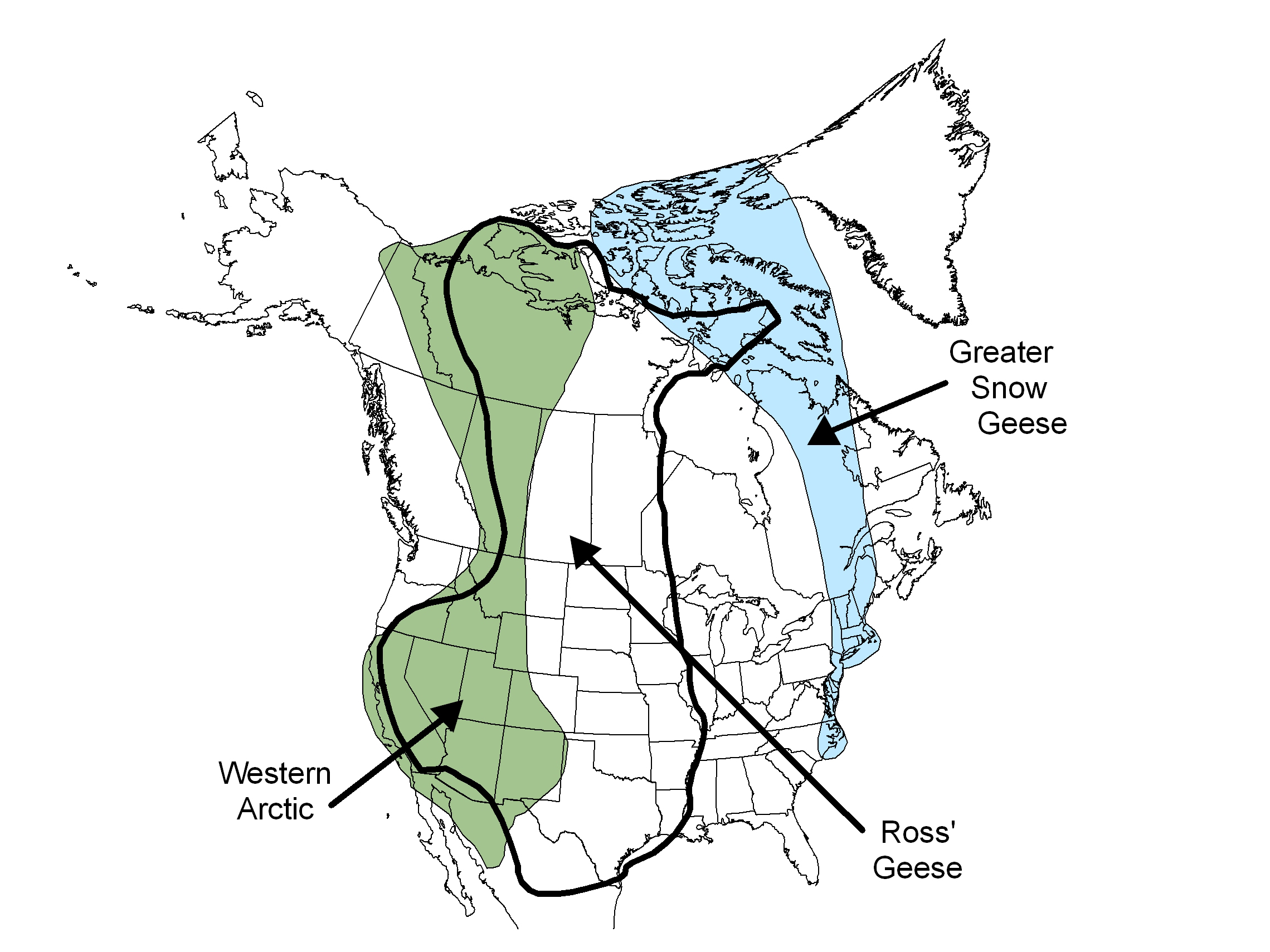

The Atlantic Flyway is the route snow geese take past Keith Maurer’s stomping grounds as they migrate, and they’re usually active along that route between November and March.

But there’s room for complexity within that time period, and “weather definitely affects bird behavior,” says Chandler Sawyer, habitat manager for Audubon’s Pine Island Sanctuary and Center. “I wouldn’t say it’s weird [for Maurer to see geese and swans take off in early February], but snow geese generally do hang out a little longer.”

Over several decades the populations of these birds have grown dramatically, so there are plenty to observe in the coastal wetlands of south Virginia and North Carolina. In the annual Waterfowl Status Report issued by the federal Fish and Wildlife Service, scientists estimate 818,000 snow geese use the Atlantic Flyway, three times as many as 25 years ago.

John Stanton, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has been working in North Carolina for almost that entire time.

He says written records about geese and swan migration along the Flyway go back a century, with solid data going back decades. They show that the dates geese pack up and head north or south.

Late arrivals?

That’s not to say that migratory bird patterns haven’t been affected by climatic shifts. In the fall, if temperatures don’t drop in the northern spots they frequent, birds may not get clear signals to move to wintering grounds. That’s a hypothesis from Steve Coari at the Virginia Beach Audubon Society. “To the observer’s point, most of the migrations have been coming in much, much later this season and we’re presuming it’s because of the warmer weather that we’ve had so much of the year here,” Coari says.

And local experts including Stanton acknowledges there’s “a little bit” of evidence that snow geese are showing up in North Carolina, Virginia and Maryland somewhat later. But he says, “we need to be very cautious.”

Bottom line: it may be that the geese haven’t really left yet.

Avoiding harrassment

While Stanton says swan and geese migration generally is stable, he has noticed a couple of changes. First, he’s noticed “geese exploring new wintering areas as they seek to avoid specific disturbances.” In other words, geese and swans wanting to avoid harassment, like hunting, airplanes, or even just development, will pick up and move some miles away, and they may be doing it more often. (The human equivalent may be trying to find the good spot at the concert, while avoiding the girls with cell phones, the tall guys, and the people going back and forth to the bar the whole time.)

And second, he believes tundra swans have “broadened” their territory in North Carolina, “ten, twenty, thirty, fifty miles into surrounding areas,” possibly looking for water and food.

“Many observations, such as that one, repeated many times, will give us better data on which to base a better understanding of these and other questions,” says FWS biologist John Stanton.

So what does Keith Maurer’s observation mean?

John Stanton’s guess is that what Maurer saw was snow geese and tundra swans responding to a local stimulus or disturbance; he suspects that those birds may still be in wintering grounds nearby. But Stanton admits he really can’t know.

He says that’s why recording data is so important.

“Many observations such as that one, repeated many times, will give us more data on which to base a better understanding of these and other questions,” Stanton says. “Pioneers of the past kept records of their expeditions, and those were the basis of our understands in the natural world. They are still pertinent today to help us learn about the environment and how it may be changing.”

Photo via Flickr/hjhipster