New Orleans is no stranger to downpours and flooded streets. But this year, residents found themselves even wetter than usual.

Brooke Perry has lived in New Orleans for five years. Her home is in the Gentilly neighborhood, which stretches from below sea level to the shores of Lake Pontchartrain. Some days this spring, she said, flooding made it difficult to get to and from her job as a city planner downtown at City Hall.

“I live near an intersection that floods really badly, so sometimes I just have to call my fiancé and ask him, ‘Can I get home? How’s the road?’” Perry said. “I have had to just go to a friend’s house for an hour or so and wait until the flooding goes down.”

The spring and summer of 2017 saw record-breaking precipitation totals across the Gulf. In April, Louisiana experienced 1.17 more inches of rainfall than normal. In May, 4.2 more inches fell on the state than is usual. In New Orleans, late spring through the end of the summer was the rainiest period on record since 1947.

Flooding at the intersection of Dreux & Elysian Fields and along Western Street in Gentilly.

And ISeeChange observers noticed too. Starting in May and culminating in extensive flooding in late July and August, the average afternoon rain events were unusually intense and revealed significant problems with the city’s drainage and pumping systems (stay tuned to ISeeChange for more on this topic soon).

Scientists are working on developing new forecasting tools to predict when rainy seasons like this are coming. Which would be helpful to residents like Perry. In her experience, the rain in her area comes out of nowhere. “I feel like a lot of our storms just come up out of the Gulf,” she said. “They’re not forecasted, they just suddenly appear.” Perry wonders why that happens and how she can better understand when storms are headed her way.

According to Da’Vel Johnson, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service, pop-up storms are a typical pattern in New Orleans because of two main factors: moisture and heat.

The air over the Gulf of Mexico is full of moisture, especially during the spring and summer months. When the land heats up faster than the surface waters of the Gulf of Mexico or Lake Pontchartrain, off-shore breezes will initiate afternoon thunderstorms.

“If it’s hot and humid during the day, odds are pretty favorable for showers and storms,” Johnson said.

But when does the typical pattern veer toward extreme?

Dr. Raymond Schmitt, a physical oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, is pioneering research that helps understand just how much moisture is headed the Gulf’s way. He does this by studying surface salinity levels, a measure of the saltiness of the surface of the water, in the Atlantic Ocean.

In one study, Schmitt analyzed the connection between ocean salinity and rainfall for major precipitation events in the southern U.S. in 2015.

“We noticed that the sea-surface salinity levels off the U.S. East Coast were higher than normal,” Schmitt said. “That was associated with a lot of spring rainfall in the South.”

High sea-surface salinity, Schmitt explained, means that water has evaporated from the ocean and is in the atmosphere. This pattern is intensified by climate change. A warmer atmosphere can hold more water, so as the climate warms, the air absorbs more water from the ocean.

“This water cycle intensification also leaves a signature in the salinity,” said Dr. Laifang Li, a climate dynamics researcher who studies ocean salinity and weather patterns with Schmitt. “Over the ocean, the salty region is getting saltier and the fresh region is getting fresher.”

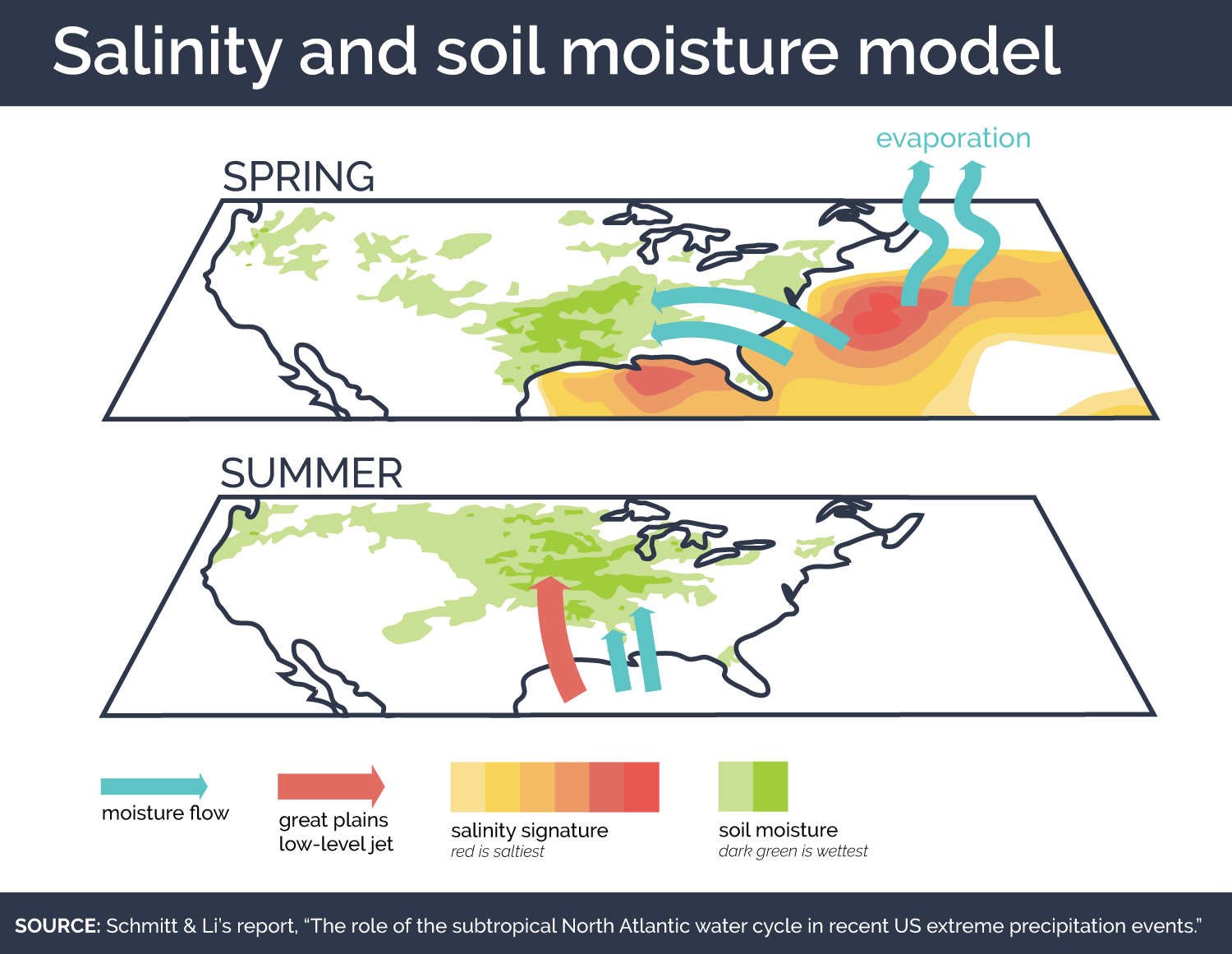

Li said that the observed relationship between salty waters off the east coast of the U.S. and rain in the Gulf is strong: The evaporated water from the ocean travels along the prevailing winds as moisture in the air, and it condenses into rain when that air reaches the Gulf states.

Then, Li and Schmitt say, an even more interesting pattern emerges. Roughly three months after surface salinity is high and the Gulf experiences precipitation, states across the Midwestern United States can expect to see more rainfall too.

This is because of all the moisture that collects in the soils of the southern states.

Intense water accumulation in less than half an hour flooding results.

“Once you have a certain amount of moisture in the soil, it can almost act like the ocean, so the water can get recycled locally,” Schmitt said. That means that warm air can pull water from the soil just like it does from the Atlantic.

In the spring and summer months, there’s a strong connection between weather in the Gulf region and weather in the Midwest, because of a river of air in the lower atmosphere known as the Great Plains low-level jet. It moves from south to north, bringing warm air and moisture to the Midwest. So after heavy spring rainfall dumps water into the soil of the Gulf, the jet helps carry that moisture up into the Midwest where it falls as rain.

Bryan Peake, a service climatologist at the Midwest Regional Climate Center, notes that swings the region saw different extreme precipitation swings this past season. “You’re getting these heavy rainfall events and you’re getting these very dry events.”

He notes that it’s typical for the Midwest to see heavy, early-season rains because warm air is coming up from the Gulf and meeting the remnants of a cold, Midwestern winter. Precipitation during the spring and summer months are important in the Midwest as most of the region is between 50 and 90 percent farmland.

Schmitt hopes that he can develop his research into a forecasting tool that will help meteorologists, people like Brooke and farmers in the Midwest better understand what to expect from spring and summer skies. His team recently received funding from the National Science Foundation to develop salinity-based prediction tools.

Schimtt and Li’s research serves as a reminder of how interconnected climates of different regions can be. As climate change continues to alter weather throughout the U.S., flooding in the Gulf is not something Midwesterners can ignore.

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover art by Shawn Fink/ ISeeChange and Creative Commons