In the early 1940s, Suzanne Hornick’s family bought a bit of land in Ocean City, New Jersey where Hornick herself now lives. I’ve been sitting on this same couple square grains of sand my whole life,” she said. “I don’t like any other beach, I’m attached to my own little one.”

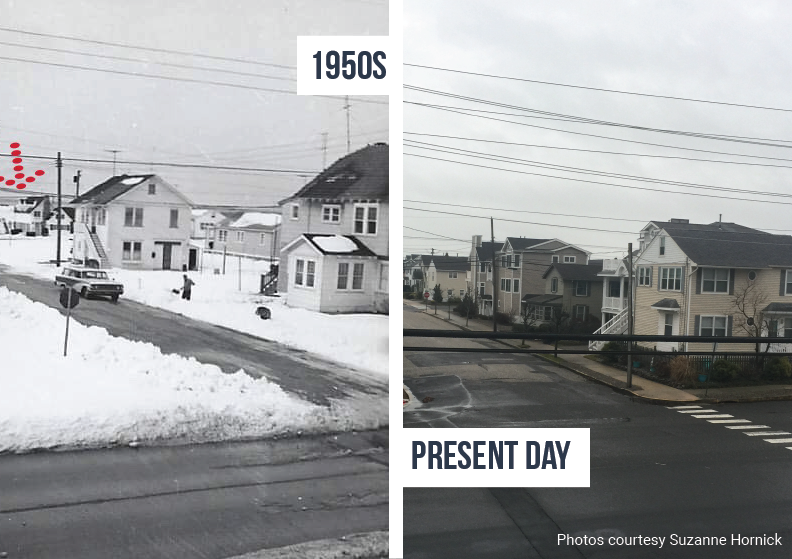

As the barrier island and nearby wetlands were developed in the 1980s and sea levels rose, she watched parts of the island sink into floodwaters. After Hurricane Sandy devastated the New Jersey coast, Hornick watched towering homes replace traditional cottages. As the years went by, the flooding got worse.

During one rainstorm, Hornick was at a gathering at a friend’s house. Floodwaters trapped her there for hours and the group of friends began complaining about being constantly inundated by water. “Next thing you know, we’ve formed a committee,” she said.

In 2015, the Ocean City, NJ Flooding Committee was born as a network of neighbors, mostly organized through a Facebook group.

“This all started because I had a big mouth,” said Hornick, who has managed the group for the last four years. “I wanted to make the only asset I had safe, livable and appreciable for my children.”

As the island continued to flood — even on sunny days — the network grew in size and influence. Development of new homes continued, while some of the original committee chose to leave the island. “They just felt like they needed to get off before it was too late,” Hornick said. Residents who stayed have worked with scientists, documenting the combined effects of storms and tides on ISeeChange, and challenging their local government to reduce flooding.

Global Trends, Local Lessons: Infrastructure and climate change

Since Hornick’s family moved to Ocean City, coastal communities on the East Coast have become more vulnerable to flooding due, for the most part, to three main changes: more development, more rain, and sea level rise.

As of the last census data from 2016, coastal communities along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts continue to grow. Between 1970 and 2010, the coastal population in the U.S. grew by 34.8 million people, a 39% increase. To accommodate more people living on the coast, wetlands and other green spaces turned into developments. This increased stormwater runoff and reduced the amount of land available to hold water during floods.

Meanwhile, climate change has brought the dual flooding threats of more-intense rain and sea level rise to the coast. Climate change increases flood vulnerabilities through more intense rainfall. According to the National Climate Assessment, “Increased evaporation rates lead to higher levels of water vapor in the atmosphere, which in turn lead to more frequent and intense precipitation extremes.” This trend is particularly strong in the Northeast which saw a 38 percent increase in the amount of total annual rainfall coming during the heaviest rain events from 1901-2016.

Sea level rise has also raised flood risk on the coast. According to the 2018 National Climate Assessment, “Global average sea level has risen by about 7–8 inches since 1900, with almost half this rise occurring since 1993.” The sea is likely to rise another one to four feet from it’s level in 2000 by the end of the century. Higher seas mean more flooding, particularly in low-lying coastal areas like Ocean City. According to research by Climate Central, Ocean City, New Jersey experienced 125 more flood days between 2005 and 2014 than between 1995-2004.

Tidal flooding from sea level rise is consistently getting worse said NOAA oceanographer William Sweet. “This year will be a record breaker, but the fact of the matter is that last year was a record breaker in many of the same areas, and the year before was a record breaker, and the year before that was a record breaker and the year before that,” said Sweet. “That is the sea level rise story.

And that same story is seen up and down the east coast. Amanda Lyle lives on Bogue Sound in Newport, North Carolina. Streets in Lyle’s community flooded from high tides during a November nor’easter that sat just off the coast for days. The community is also still recovering from flooding and storm damage that occurred during Hurricane Florence in September 2018. Lyle said that her neighbors who have lived on the sound for decades have noticed more frequent tidal flooding, and that her father-in-law, who is a surveyor nearby, has seen low lying areas and property boundaries go underwater. The small marina in her neighborhood is trying to adapt to higher water levels.

“There are little piers between the boat slips and a walkway that’s along the seawall, and more and more, it seems like at least once a month, those piers are completely underwater during high tide,” Lyle said. “But now that they’re underwater so much we’re about to rip them out and build them higher.”

When storms, like the November nor’easter in North Carolina, hit during high tide, the winds from the storm can push water up onto the coast, like storm surge during a hurricane. And high winds alone can trigger flooding. “Strong, we call them northerly winds, will cause water to pile up,” Sweet said.

As part of a project to understand what future flooding might look like in Boston, Massachusetts, Sylvia Scharf, who works at the New England Aquarium in Boston, gathered a few of her colleagues and went out to take photos of October king tide flooding. King tides, also called perigean spring tides, are the highest tides of the year. They occur when the moon is closest to the Earth and either full or new. There are typically three or four king tides each year and they occur in the spring and fall. Scharf and others were collecting photos to help local decision-makers understand what areas might be most vulnerable as sea level rise continues to increase the severity of high tides.

The king tide Scharf observed in October flooded parks and beaches. She said that, in an attempt to adapt to more frequent flooding, one of the parks had moved the kids’ playground further from the water.

On their king tide hunt, Scharf and her colleagues also drove down Morrissey Boulevard, a road that crosses an inlet and regularly floods. It was flooded that day, but Scharf realized that the flooding wasn’t coming over the sidewalk that runs between the road and the water. Instead the water was coming up out of storm drains. “There was a moment where I was looking, and there was somebody out for a jog running on the sidewalk totally dry next to the flooded street with the ocean on the other side of him,” she said.

The city is trying to learn how to update stormwater infrastructure to better hold up to climate change. “Boston is really having a lot of these conversations,” Scharf said. “I think the challenge is that there isn’t actually always money behind the conversations, or there’s not remotely the amount of money that’s necessary. We have an old city with old systems, old infrastructure. I mean we’re famous for our potholes already.”

Learning from Ocean City

Back in Ocean City, Hornick is no stranger to hitting obstacles in updating stormwater infrastructure. Since the founding of the Ocean City, NJ Flooding Committee, Hornick became a regular attendee of city meetings where she demanded they work to reduce flooding.

“The relationship between my group and the city got very contentious,” Hornick said. She was angry. She was loud. She got kicked out of meetings. “When you’re ruining my life and my quality of life I’m going to be not happy.”

Harriet Festing of the Anthropocene Alliance reached out and told Hornick that she was trying to organize flooding communities across the U.S. into a big network so they could better advocate for change. Through that partnership, Hornick was introduced to the American Geophysical Union’s Thriving Earth Exchange program which helps connect communities with scientists to solve local problems. ISeeChange is also a partner tool for the Thriving Earth Exchange, allowing networks of neighbors to gather stories and data to collaborate with scientists to analyze their data.

So Hornick’s group teamed up with researcher Tom Herrington, the director of the Urban Coast Institute at Monmouth University, and that changed everything. “When Tom came in, he was able to sit down with us in a meeting and bridge that gap between the city and my group and make it more amicable,” Hornick said. “Because of that, we have a voice in our city government.”

What has made Herrington particularly helpful, Hornick said, is that he grew up in Ocean City. “It’s not like a scientist just coming in and saying, well I have empirical knowledge that I can impart to you people,” Hornick said. “Tom says, ‘Oh I remember that on 52nd street. I know those trees. I understand that current and how it hits the bulkheads by the airport because I lived there.”

Armed with a deep understanding of the community, Herrington worked with Hornick to encourage community members to document the flooding that they were seeing. He helped distribute a handful of rain gauges across the island and explained the threats of sea level rise and possible solutions at community meetings.

Herrington has been analyzing rain totals, tide levels, and flooding photos posted on ISeeChange. In the past year, the community has recorded nearly 50 flood events. The posts showed that:

- Relatively minor rains can cause flooding.

- Moderate high tides alone can cause flooding.

- When combined together, moderate high tides and rain cause severe flooding.

The community will continue collecting data on ISeeChange to provide more insight.

“The city has been forced to make changes,” Hornick said. Approximately twenty five million dollars has been invested in stormwater reconstruction projects on the island already, and the city has budgeted another $25 million in the next five years. So far, the investment has been put into traditional gray infrastructure projects like pumping stations and giant catch basins (“I could fit my Chevy Suburban in one, that holds a boatload of water,” Hornick said).

So this fall, when ISeeChangers from North Carolina to Massachusetts reported major high tides and flooding, the street in front of Hornick’s house remained dry. While there is still more work to be done in Ocean City, Hornick believes that the lessons her community has learned can translate to other areas dealing with coastal flooding.

High tide in ICWW SATURDAY, Nov. 16th as nor’easter was strengthening offshore.

Hornick has been happy with how the changes have worked so far. Her street hasn’t flooded in almost a full year. But just because that infrastructure is working now, doesn’t mean it will be able to handle even higher seas and more intense rain. As such, Herrington has talked to community members about the need for other types of changes as well, like living shorelines and bringing more green space back to the island. “He’s giving us the tools to have a better future,” Hornick said.

Hornick recommends that other coastal communities dealing with flooding first find out what they don’t know by reaching out to experts and scientists like Herrington, and she emphasized the value of scientists who already have a relationship to the community. Then, she said, gather data via stories and photos of flooding alongside rain totals to create a concrete record of the issue. Once a community has a good sense of the problem, she said, it’s time to go public with it.

In Ocean City, they put lawn signs up during peak vacation times that read “Fix our flooding now,” spoke at city meetings, sent letters, and sought press coverage. This is not an easy task. Currently, Hornick estimates that she spends 25-30 hours a week on the Ocean City, NJ Flooding Committee and that it used to be twice as much. “When it rains, forget it, all bets are off,” she said.

“But it’s ok. Somebody’s gotta do it. We’ve got to make this right, and we can.”

If you live in Ocean City and want to help document storms and flooding, join here.

If you live in another coastal community and want to begin creating a record of flooding, join us on ISeeChange and reach out to community@iseechange.org with any questions. In particular, we’d love to hear from residents in North Carolina experiencing flooding as we are working with the Coastal Review Online to distribute five new tidal gauges in 2020.

And stay tuned, ISeeChange Miami is coming in 2020.

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections.

Cover photo by DVIDSHUB via Flickr.