ISeeChange is working with AdaptNY and public radio station WNYC on a project to observe heat impacts in Harlem, NY. Check out this story from our friends at AdaptNY about the ways hot weather harms the health of New York residents.

And we’re sharing below – with permission – a report from reporter Sarah Gonzalez on who’ s vulnerable to heat impacts and how they observe them, or fail to.

After sitting in her un-airconditioned fifth-floor apartment as the temperature surpassed 90 degrees Fahrenheit for several days in a row, 69-year-old Helen called 911.

“I couldn’t deal the heat,” she says with some difficulty. “It was too hot for me, and then I had feel weak.”

An ambulance brought her from her building in East Harlem to Mount Sinai Hospital, where she was admitted for heat exhaustion. She has a few medical issues, including a stomach problem. And her daughter says she’s stubborn: She doesn’t drink water when she knows she’s supposed to.

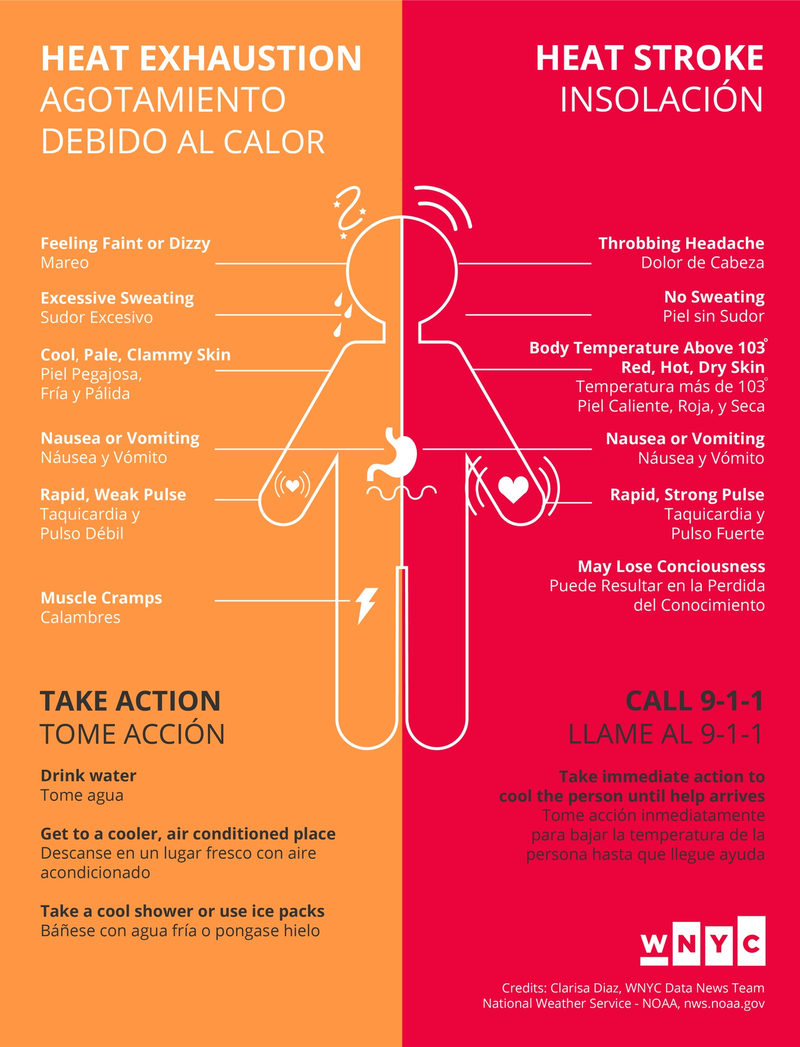

“My head start to hurt, and then I start to throw up and I had feel a little dizzy a little,” says Helen, a fictitious name made up to protect her privacy.

She talks from the hospital bed with her eyes closed. She doesn’t want to leave the hospital and go back to her hot apartment.

“Oh, God. The fan ain’t doing no good, at all,” Helen says. “With this heat? No, I can’t do that.”

Elderly people like Helen, young children and others with pre-existing medical conditions are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat. Public health professionals say air conditioning — even just a couple minutes of it — is the best way to lessen the effects of extreme heat.

As of the first week of August, just 13 patients this summer arrived at Mount Sinai Hospital complaining specifically about heat. But the heat played a less obvious role in many more ER visits — about a dozen a week, according to the hospital.

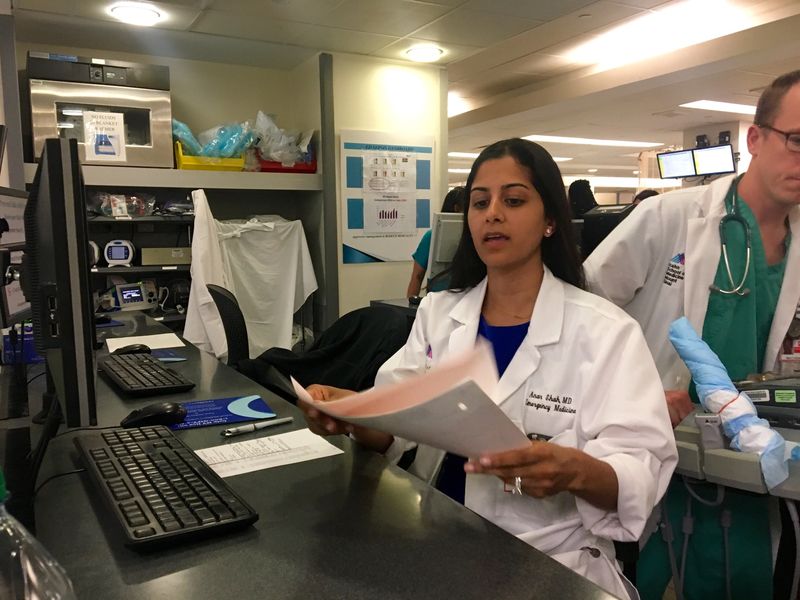

Dr. Anar Shah, an emergency room doctor at Mt. Sinai, says patients don’t often prepare for heat waves the way they do for other natural disasters.

“I don’t know why people don’t take it as seriously,” Shah said. “I think that it’s not as obvious when you look outside your window that there is something dangerous that’s happening in the environment.”

The heat is mainly a problem among the poor who can’t afford AC, says Eric Klinenberg, a sociologist at New York University and author of Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago.

“These are people who are invisible all the time,” Klinenberg said. “And so when they’re suffering invisibly during a heat disaster, it’s hard to get people to take notice.”

Convincing the general public that air conditioning is a necessity for some people is incredibly difficult, Klinenberg says.

“Air conditioning is a luxury, and not a necessity, almost all of the time,” Klinenberg said. “But there are times during our hot and humid summers when air conditioning can make the difference between life and death. And I say that as someone who is very critical of Americans’ over-use of air conditioning.”

Part of the problem, he says, is that cities undercount the role that heat plays in hospital visits and deaths.

But it is hard to determine that role precisely in practice, officials say.

What’s a ‘Heat Death’?

Medical examiners in New York, Baltimore and Chicago say that the only sure way to know if someone died from hyperthermia — the medical term for overheating — is if their body temperature is taken right before they die, and the temperature is around 104 degrees.

If you don’t have that proof, David Fowler, the chief medical examiner in Baltimore, says determining a heat death becomes largely subjective.

“It’s not an exact science,” Fowler said. “It’s a very, very complex process which requires an awful lot of experience and careful weighing of every single case.”

Fowler says he takes a liberal approach to classifying heat deaths. He said he doesn’t want to downplay the true impacts of heat because the statistics he sends to the health department influence policies, such as when cooling centers should open.

“So there are all sorts of ramifications that will affect the community and the individual family members if this is not done correctly.”

In New York City, the Department of Health and Mental Hygeine said 25 people died directly from heat stress in 2013. But the city admitted that doesn’t capture the “total mortality burden” of extreme heat.

They estimated that number to be 140 deaths.

“We should think about air conditioning as something maybe akin to a prescription,” said Patrick Kinney, an environmental health science professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

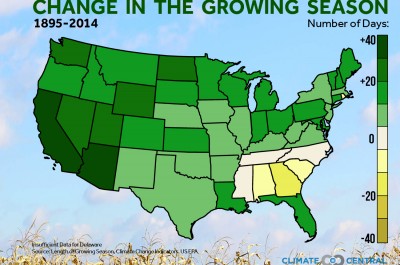

Like Klinenberg, Kinney is acutely aware of the way air conditioning contributes to global warming, but said it is an essential tool for public health.

“If you take a couple of big office buildings in New York City that may be air-conditioned all through the night when no one is working in them,” he said, “and you just used some of that air conditioning to help the people who are most vulnerable, we wouldn’t worsen the climate change problem. But we would save a lot of lives, potentially.”