Twice a day, Lorne Covington walks his dogs around his 20 acres in Skaneateles, New York. Covington’s lot is mostly wooded, with a four-acre wildflower meadow. Typically in July, he sees wasps, carpenter and bumble bees buzzing around the flowers. This summer the buzzing was for all practical purposes non-existent.

“We had a bumper crop of wildflowers this year,” Covington said. “But unlike previous years, there were just no bees.”

Covington isn’t alone in observing a lack of pollinators this summer. Sue Stroud reported fewer bees in Brentwood Bay, British Columbia. Judy Donnelly saw fewer bumble bees and wasps in Windham, Connecticut. And in Paonia, Colorado, Amber Kleinmann’s honey bees have been producing less honey than usual.

Like Covington, honey bee expert Peter Borst, a retired Cornell professor and the president of the Finger Lakes Bee Club in Ithaca, N.Y., has noticed changes and says he thinks that the decrease in native pollinators is the result of warmer late-winter temperatures the past few years. These “false” and early springs can wake the bees just in time for spring cold snaps to kill them.

“I would put it down to (A) climate change and (B) variations during the winter,” Borst said, “Not necessarily cold or hot — just weird.”

He added that it’s hard to say for sure if the pollinator population has decreased — there’s simply no easy way to count them.

“It’s very hard to know how to census pollinators,” agrees Nickolas Waser, who studies plants and pollinators at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Gothic, Co. The biology professor at the University of California-Riverside studies another climate threat to pollinators that has been particularly problematic in the west this year: drought.

Much of Waser’s research has focused on a plant called scarlet gilia and its main pollinator: hummingbirds, considered an iconic signal of summer in the upper Rockies and prominent feature in the logo of Waser’s lab.

In the middle of a seven-year study of the plant and hummingbirds, Waser and fellow researcher Mary Price stumbled upon a surprising paradox. The years that the scarlet gilia saw the highest rate of hummingbird visits were also the years that the plants received less pollen than average.

“That was a total surprise.” Waser said. “You want nature to show you secrets.”

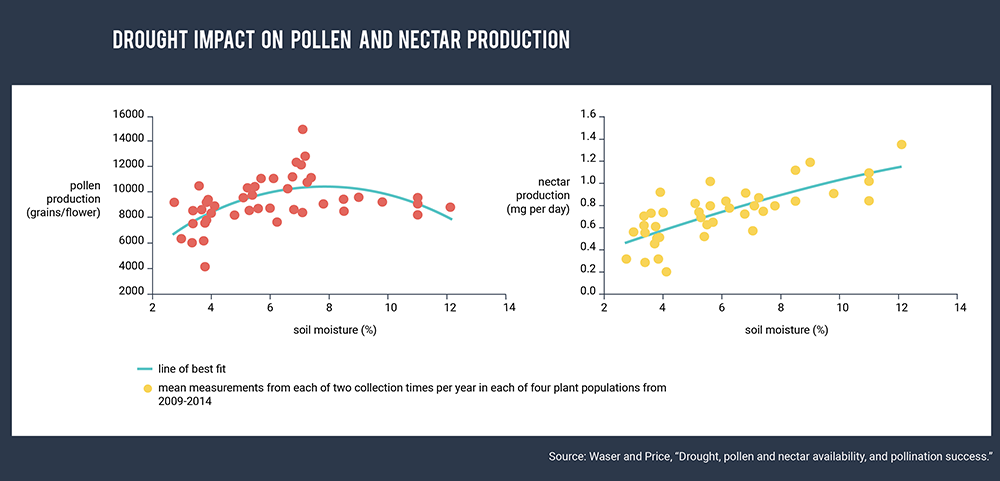

The researchers revealed the secret through further research. Waser and Price realized that the years with high visitation and low pollen counts coincided with regional drought. They set up a greenhouse experiment and induced dry conditions to see the effects on the scarlet gilia plant. The flowers produced less nectar and pollen.

That means that hummingbirds have to work harder and visit more plants to get the nectar that they need when conditions are dry. Flying flower-to-flower makes them burn even more energy, thus needing even more nectar at a time when supplies are low.

The cycle has compounding effects. This year has been especially dry in Colorado and the rest of the southwest.

“Our plants certainly have shut down this drought summer, and aborted most of their fruits,” Waser said.

Scarlet gilia aren’t the only plants affected by water stress.

Paul CaraDonna, an ecologist who works for the Chicago Botanic Garden, Northwestern University, and the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, spent this summer collecting nectar from plants in the Colorado mountains not far from Waser and Price.

Using a light refractor to analyze the ratio of sugar to water in different nectars, CaraDonna and his team noticed something strange: the nectar had an extremely high sugar concentration, up to 80 percent sugar in some cases.

Based on Waser and Price’s research, the team expected the amount of nectar in the flowers to be relatively low with drought conditions. They knew that sugar concentration would likely go up as the total amount of nectar decreased, but such a high concentration was unexpected.

“The values just seemed so outrageous,” CaraDonna said. “My student Atticus kept saying, ‘I don’t know if the refractometer working cause the values are so high,” They tested the device: It was working just fine.

Then, in mid-July, the area got a few rainstorms. For four different plant species, CaraDonna had nectar data from before and after the rain events. After the rain, the sugar concentration was lower, but the amount of sugar remained the same. It was the water levels that had changed.

That finding connects the dots: when plants are drought-stressed, they’re unable to put much water into the nectar production process. The net result is sweeter nectar, which pollinators like bees love, but there’s not enough being made. This summer a fellow researcher described the bees as “flighty,” meaning they couldn’t seem to relax and stay at flowers as long as usual.

For bees, less nectar means fewer calories, which can mean smaller colonies and fewer offspring, CaraDonna noted.

While plant-pollinator relationships can be resilient in the face of seasonal variations in climate, CaraDonna wonders just how much stress they can take. With models predicting that climate change will make extreme drought more common in the Southwest, we may soon find out.

“Everyone’s a little bit worried if we get two of these really dry years in a row,” said CaraDonna noting the parallels to people and fire dangers this year in the west.” You’re already stressing out a lot of these organisms and it’s hard to imagine what they’d do when you repeatedly stress them out.”

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover photo by USFWS Mountain Prairie.