Betsy Wilkening’s daughter was looking forward to Tucson’s sunny weather when she came home for the holidays from the UK, where she’s studying at Cambridge. She got some sun — but also a generous drenching. Betsy joked that she’d brought the wet weather with her.

Between December 17 and the first of the year, Betsy’s rain gauge in northwest Tucson recorded 2.3 inches of moisture. Winter rains aren’t unusual, but it seemed like a lot all at once. “What really struck me was we got so much rain in just that few week period,” she says. Over the whole year, Tucson gets only around 12 inches.

We received 2.30″ of rain (about 1/4 of our annual rainfall) between 12/17/16 and 1/1/17.

In early January, Betsy noticed something else odd: a lizard sunning itself in her front yard. Many lizards and other desert animals, such as snakes and tortoises, hibernate in the winter months. “Usually we don’t see lizards until at least February,” Betsy says. But this day in January was nearly 80 degrees, around 15 degrees warmer than average.

Winter — in the desert?

Winter is the season of relief in the Sonoran Desert, when temperatures settle into a remarkably pleasant range. Daytime highs from December to February are typically in the mid to high 60s. At night, temperatures can dip below freezing, particularly in the northern parts of the desert, which supports more cold-tolerant plants than the southern sections. But freezing temperatures hold only a loose grip on the place.

“One general rule of thumb is that the boundary of the Sonoran Desert is at least substantially defined by where freezing temperatures don’t occur for more than 24 hours (at a time),” says Jeremy Weiss, a climate scientist at the University of Arizona.

The Sonoran Desert gets about half of its rain in the winter months, somewhere between December and late March, says Zack Guido, a researcher at the University of Arizona’s Institute of the Environment. The other half comes during the summer months. Those storms — called monsoons — tend to be heavy and isolated; the skies might pour on the east side of Tucson and be sunny and dry on the west side. The winter storms, by contrast, arrive as large fronts that deliver moisture across large swaths of the landscape.

Rains are tricky to predict

This winter, Arizona has benefited from some of the same tropical moisture that has dumped snow and rain on California, helping to ease drought conditions in both states.

But how climate change might be affecting winter rain in the Sonoran Desert, and how precipitation patterns might change in the future, are pretty uncertain, Guido says. “We do have a fair amount of variability, which makes it hard to detect a signal from the noise.” Another big source of uncertainty is the El Nino Southern Oscillation, a cyclical warming of the Pacific Ocean that is usually associated with wet winters in the Southwest.

Still, he believes it is reasonable to expect that heavy rain events will get even heavier in the future, because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture. He’s just not sure whether such a trend is already apparent. “These events are by nature extreme, so there’s very few of them, and we don’t have a really long observational record,” he explains. “So understanding statistically significant changes is problematic.”

We do know the Southwest is heating up

In the Southwest as a whole, the first ten years of this century were warmer than any other decade in the previous hundred years, with average temperatures increasing by about 1.6 degrees F. Heat waves have become more common, and in summer, scorching temperatures can prove deadly. Last June, during a weekend of record-breaking heat in Arizona, four hikers died.

But winter is warming up, too. In 2005, Weiss co-authored a study that documented a decrease in the number of days when temperatures dropped below freezing in the Sonoran Desert. Data from one weather station showed that the season free of freezing temperatures had lengthened by about a month. Similarly, National Park Service data from Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument shows that the number of freezing days dropped from around 28 per year in the 1950s to 5 in 2006.

These changes could reshuffle plant communities in the Sonoran Desert, Weiss says, with native — and invasive — species that are sensitive to cold creeping into more northern areas. One of those invaders, buffelgrass, is prone to wildfire, which iconic plants like the saguaro cactus aren’t adapted to — and might not survive. The desert’s northern boundary could even expand as winter warms.

And what about that lizard in Betsy Wilkening’s yard? Brian Sullivan, a herpetologist at Arizona State University, says it is unusual to see the species Betsy spotted — a desert spiny lizard — out and about in January.

Lizards rely on the sun to regulate their body temperature. Some smaller lizards stay active year-round in the Sonoran Desert; their size makes it easy for them to warm up quickly in even the winter sun and go about their business. But desert spiny lizards are fairly hefty, and it takes a lot longer to warm their bodies in the sun — too long, perhaps, to escape a predator. So they spend the cooler months hibernating, usually emerging again in February or March.

Still, Sullivan says it’s not unheard of for desert spiny lizards to pop out on warm winter days, nor is it cause for concern. He’s not aware of any studies that have shown Sonoran Desert lizards shifting their mating or hibernation patterns in response to warming temperatures, and points out that they are adept at navigating temperature extremes. In the summer, for instance, they’re active in the morning and retire to the shade as the temperature climbs to avoid getting baked.

So keep watch for signals in the desert

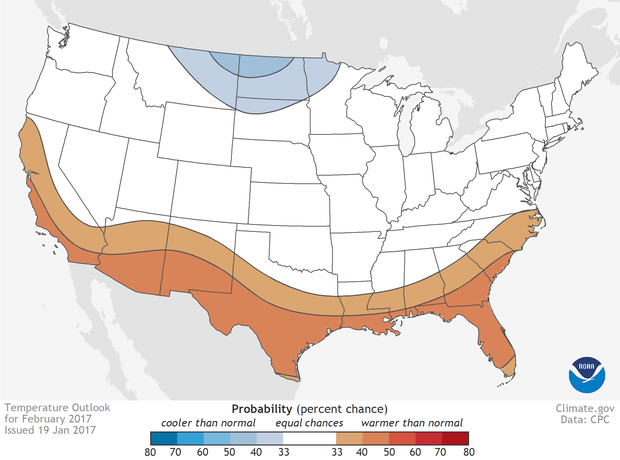

It looks like more warm weather is on its way: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s Climate Prediction Center is forecasting above average temperatures in the Southwest over the next three months. We want to know how warm temperatures impact you and your community.

When warm Arizona winters coincide with harsh Canadian ones, does Arizona’s economy get a boost from cold-weary snowbirds? Do the patterns of migration from the southern border change with the weather? Are you turning your AC on earlier in the spring, and paying higher energy bills?

Let us know. We’re listening at ISeeChange.

Photo courtesy of NOAA’s Small World Collection: “Rare Desert winter snow on giant saguaro cactus of the Sonoran Desert, byPete Gregoire, January 1, 2015. “