Walking through the woods near her home in Marlborough, Connecticut, Matylda Biskupski couldn’t help but notice that the forest seemed bare. “There’s very little shade. It’s very weird,” said Biskupski, a freshman at Rham High School.

Throughout the summer, gypsy moth caterpillars munched on the forest’s green canopy, leaving trees across Connecticut and Rhode Island leafless. According to Heather Faubert, who runs the Plant Protection Clinic at the University of Rhode Island, the caterpillars prefer oak and apple leaves when they’re young. But as they grow and the population expands, they’ll feed on just about any kind of tree.

There were so many caterpillars that Biskupski could hear them. “They poop a lot,” she said. ““It would sound like rain.”

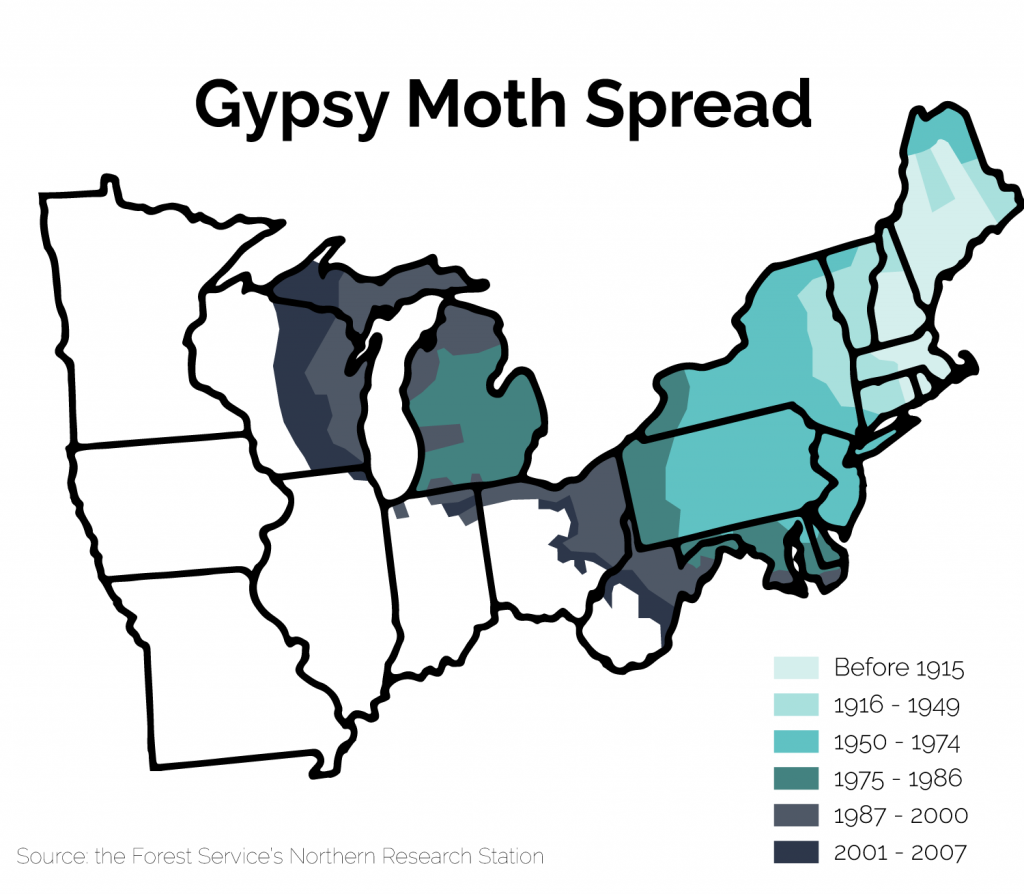

The moths are an invasive species in the United States. Nearly 150 years ago, an artist and astronomer named Etienne Leopold Trouvelot returned to Massachusetts from a trip to France with several gypsy moth egg masses. According to the U.S. Forest Service, Trouvelot was an amateur entomologist and was experimenting with cultivating the egg masses on trees in his yard. During his experiment, a few of the caterpillars escaped, changing American forests forever.

Since the late 19th century, states and the U.S. Forest Service have been trying to control gypsy moth outbreaks and their spread across the country.

The main threat to the gypsy moth in North America is a Japanese fungus called Entomophaga maimaiga. But the fungus dies during prolonged drought, and the Northeast has experienced unusually dry, early springs and dry, hot summers during the past three years.

“The fungus that usually kills the caterpillar was almost non-existent,” Faubert said.

And that means the gypsy moth has been thriving.

In Windham, Connecticut, Judy Donnelly also saw a boom in the caterpillar population.

“At their worst, the shady side of the trees were completely covered with caterpillars,” she said.

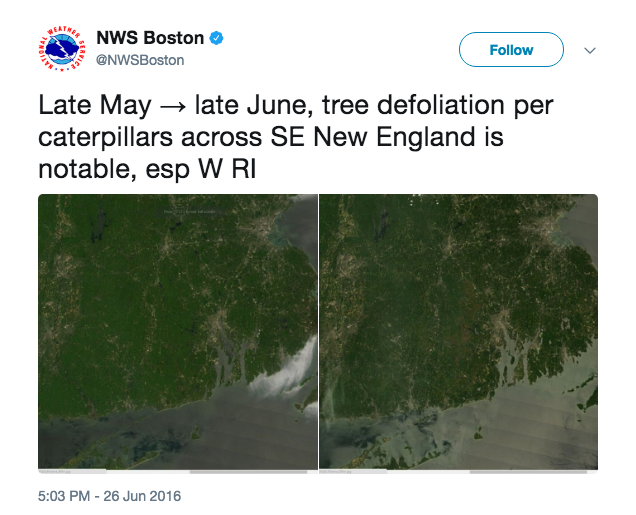

The caterpillars pose a threat to forests. In large numbers, they can completely defoliate trees and even forest understories. In 2016, over 350,000 acres of Massachusetts forests were defoliated by gypsy moths. This defoliation stresses the trees and can kill them.

“We usually think that trees can tolerate two years of defoliation, and then the third year they will die,” Faubert said. “But that’s really just a rule of thumb. What we found last year was trees got defoliated, and I think due to the drought, it really stressed out a lot of trees, and a lot of trees died last year.”

Donnelly also lost several trees this year. When she called to have them removed, it was difficult to schedule an appointment. “I guess there’s a lot of people who need trees down,” she said.

It’s left her wondering how to protect her trees in the future. “Now what?” Donnelly asked. “The fungus apparently is very effective, but if it’s dry then what do we do?”

“I can’t go out and water the woods.” she added.

Managing the moths

There’s not a lot that individuals can do to combat gypsy moth populations in the midst of an outbreak. Faubert says the best bet is to keep the trees wet, but she admits that’s easier said than done.

But you have a few trees in particular that you want to keep safe, try to keep them watered to give the fungus a chance to act, Faubert said.

Faubert also noted that some people attempt to control the population by spraying a BT insecticide, which should have a limited effect on insects other than moths, or by knocking down any egg masses they see. The problem with these efforts is that the BT sprays last only for a few days, and there are thousands of egg masses.

The only guaranteed relief comes from rain. Luckily, this summer brought relief to drought-stricken areas throughout the Northeast.

“It was a lot rainier this year,” Bisupski said. “We saw the fungus.”

In Rhode Island, Faubert witnessed a major die-off of gypsy moth caterpillars on June 23. But she said, the fungus takes all season to build up to full strength, so the real benefits of a wet summer should be felt next year — especially if next spring is wet.

But wait, what caused the drought?

The relationship between climate change and precipitation is complicated. As the climate warms, overall precipitation has increased. But rainfall is concentrated in quick, extreme events instead of spread out over time. Winters in the Northeast have also seen a decrease in snow coverage, which can contribute to a drier spring season, since there is less snow melt.

According to Jeanne Brown, communications and outreach manager at the Northeast Climate Science Center, summers in the Northeast are expected to get much warmer. Without action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, average summer temperatures in Massachusetts are projected to increase by 8°F. And warmer temperatures, Brown noted, mean higher potential for dry spells.

All of these factors, according to research by the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, contribute to drought in New England. “Warming and less frequent precipitation events favor an increase in drought intensity,” the report said. Which could make for fundamental changes in the iconic fall seasons in New England.

With trees increasingly damaged by insects and weird weather, Curt Newton from Amherst noticed the strange sound of dried leaves blowing in the hot and humid August breeze. “I viscerally associate that sound with cool weather and more slanting autumn sunlight,” he wrote in a post on ISeeChange.

Our maple trees are dropping their dried-up leaves like we’re deep into autumn, due to a leaf fungus called “Tar Spot.” Supposedly it doesn’t deeply harm the tree, if it’s just a one-year bloom. I hear that weather disruption — a very early spring (did we even HAVE winter?) into unusually cool and damp summer — makes Tar Spot take off.

Biking home from work tonight, it hits me — the sound of dry leaves blowing around streets and yards doesn’t belong with hot weather. I viscerally associate that sound with cool weather and more slanting autumn sunlight.

Wonder what other deep associations between weather and sight/sound/smell may be disrupted by climate change, as transitions and boundaries between seasons are stretched and reconfigured?

Bug boom? Fall feeling Funny?

Have you seen more insects or distressed trees in your backyard? Have you noticed anything unusual in the transition from summer to fall this year? Whatever you’re seeing, we want to know about it. Post your findings on ISeeChange.

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover art by “Echoe69” and “Followtheseinstructions“/Flickr and Creative Commons