Santa Fe resident Susan Swartz knew early in 2018 that the drought in her community would be punishing this year.

Winter never came, and in its absence, there was no snowmelt to feed the Rio Grande River in New Mexico. By mid-April, a ten-mile stretch two hours south of Swartz’s home had dried up. In the riverbed, only mounds of fish carcasses remained.

“I just don’t remember the river drying up this early and this quickly,” Swartz said.

Swartz, who’s lived in Santa Fe for 11 years, is accustomed to drought and thought she was prepared. She even equipped her house with three 5,000-gallon rainwater collection tanks in 2015. But this year, for the first time, they didn’t recharge. Swartz worries that she’s hit the limit of what she can do as an individual.

“Some of this is in other people’s hands,” she said. “We try to do our best. Some of it we just don’t have any control over.”

The climate science

In addition to drought, Swartz is also concerned about rising temperatures. She said temperatures hit 86°F in early May, a month earlier than usual in Santa Fe.

According to Gregg Garfin, a professor at the University of Arizona and an author of the Southwestern chapter of the 2014 National Climate Assessment, temperature increase is the driving force behind the changing climate in the Southwest. “There’s been a real strong upward trend, especially in the last 40 or 50 years,” he said.

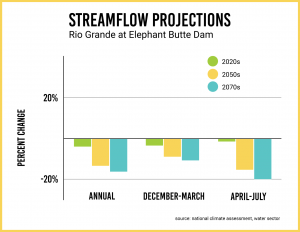

Warmer temperatures affect snowpack in high altitudes that feed into Southwestern rivers, like the Rio Grande. Garfin said that warmer winter temperatures in the region have led to a greater percentage of precipitation falling as rain rather than snow. Additionally, he noted that warmer temperatures have caused reduced soil moisture and increased evaporation in the region. That makes snowmelt less efficient in reaching rivers because some of it is absorbed by soil and air.

Another factor, Garfin said, is that winter storm tracks have shifted to the north in recent decades.

“That can help the snowpack in the northern part of the southwest region, but it deprives the southern part of the region,” he said.

Garfin expects these temperature-associated trends to continue into the future, but he noted that precipitation predictions are less certain. Some models suggest that portions of the region will see increased precipitation and some rivers, most notably the Colorado, could see increased flow.

But a 2017 study by Brad Udall of the Colorado River Research Group found that increased temperature alone could cause a minimum of a 20 percent decrease in runoff in the Colorado River basin by mid-century.

“Overall, that adds up to a picture of just less reliable surface water supply,” Garfin said.

Managing uncertain water in a desert

Questions of who gets to use water, how often, and when are complicated in the American Southwest. According to Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University,* it all dates back to when settlers arrived in the arid region and started to parse out water rights.

“They developed this doctrine called prior appropriation,* which means the person who got there first and diverted water had the senior rights,” Porter said.

Today, rights to water from rivers and reservoirs are managed between states and localities. For major rivers like the Rio Grande and the Colorado, rights are managed through agreements between states called compacts. When resources are strapped, like in the case of prolonged drought, disputes often crop up.

This March, the Supreme Court heard and decided a case involving a dispute between New Mexico, Colorado and Texas.

Porter said that getting stakeholders on the same page in water policy can be complicated, but that finding common ground is possible. Among the Colorado Compact parties, the sustainability of resources has been one of those common ground issues.

“There are disagreements, but among the seven basin states and Mexico there has been a sincere commitment to negotiate and collaborate to ensure resilience,” Porter said.

Building resilience

Resilience in Southwest water policy is an effort that combines various management strategies and conservation to make sure that water supplies and communities can endure drought.

Among Central Arizona users of Colorado River supplies, Porter said, tribal and municipal contract holders have higher priority than agricultural users, who are the first affected when deliveries are cut. Cities, tribes, and agricultural users currently are negotiating to find ways to mitigate those impacts, Porter said.**

“We still have a lot of give in the system, a lot of ability to move water supplies from one use to another,” she said.

Porter said that in her experience, conservation is just one piece of the larger puzzle of building water-resilient communities, and that higher-level management strategies* are the most effective policy.

Garfin suggested possible solutions like banking water underground to impede evaporation, treating and reusing wastewater, and desalination in cities on the coast or with brackish groundwater.

But conservation remains the foremost focus of most cities and water utilities in the Southwest.

Santa Fe’s drinking water comes from three primary sources: the Santa Fe River, the San Juan-Chama project which includes water from the The Rio Grande and the Colorado River, and an underground aquifer called the Tesuque Formation aquifer. The city also uses treated wastewater effluent to irrigate recreational fields and golf courses, control dust at construction projects, and provide water to livestock and wildlife at several facilities.

Christine Chavez, water conservation manager for the Santa Fe Water Division, said that conservation is a high priority in the city because saved water can go to other users or remain in storage.

“It’s the least expensive source of water,” she said.

Chavez’s team uses a combination of tactics to get residents to conserve water. The water utility employs rebate programs to encourage the switch to water-efficient appliances and to boost adoption of rainwater collection.

“We saved over 10 acre feet of water just in our rebate program last year,” she said. That’s about 3.26 million gallons of water. Based on daily per-capita usage data from the Santa Fe Water Division in 2016, that’s about a year’s worth of water for 25 four-person households.

The city also uses smart meters that allow customers to see how much water they’re using and where it’s going. The meters also notify residents of leaks.

“It’s just a way for them to take control of their water use,” Chavez said. “It’s one of the best things that we have for our customers.”

Looking forward, Chavez said that the question that the utility is constantly working to answer is: “How are we going to meet this demand if climate change continues to occur?”

As drought gets worse, she expects the utility may have to implement more use restrictions and raise rates.

“I think it’s inevitable that water will just become more expensive as we move forward,” she said.

Swartz worries about just that. “Water is the new gold,” she said.

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Editor’s Note: Several copy edits were made to this article on September 26, 2018, to make corrections. Spots edited are marked by a single asterisk — *. The paragraph marked with two asterisks — ** — is a substitute paragraph to better represent the views of the individual to whom the comments are attributed, and at her suggestion.

Cover art by Sara Harris Photography, Creative Commons.