In the Midwest, you know spring has arrived when tractors start to hold up traffic on the highway. But before the tractors, the ISeeChange community saw signs of early spring across the Plains and the Midwest: Butterflies fluttered through apricot blossoms in Nebraska on the first day of spring, Jessica Maldonado’s tulips bloomed by mid-March in Kansas, and in Illinois, William Lorch’s garlic has been growing since January.

For Anne DeVries, who lives in southeastern Nebraska, this spring has been one of extremes. She said that temperatures quickly jumped from cold to warm – hot enough to burn her skin in the sun – and that the rainy season feels longer this year. That left her wondering how climate change, and the wacky weather it causes, will affect farmers: “Can farmers change as quickly as the climate changes?” she asked.

Floods, droughts, heat create challenges for farmers

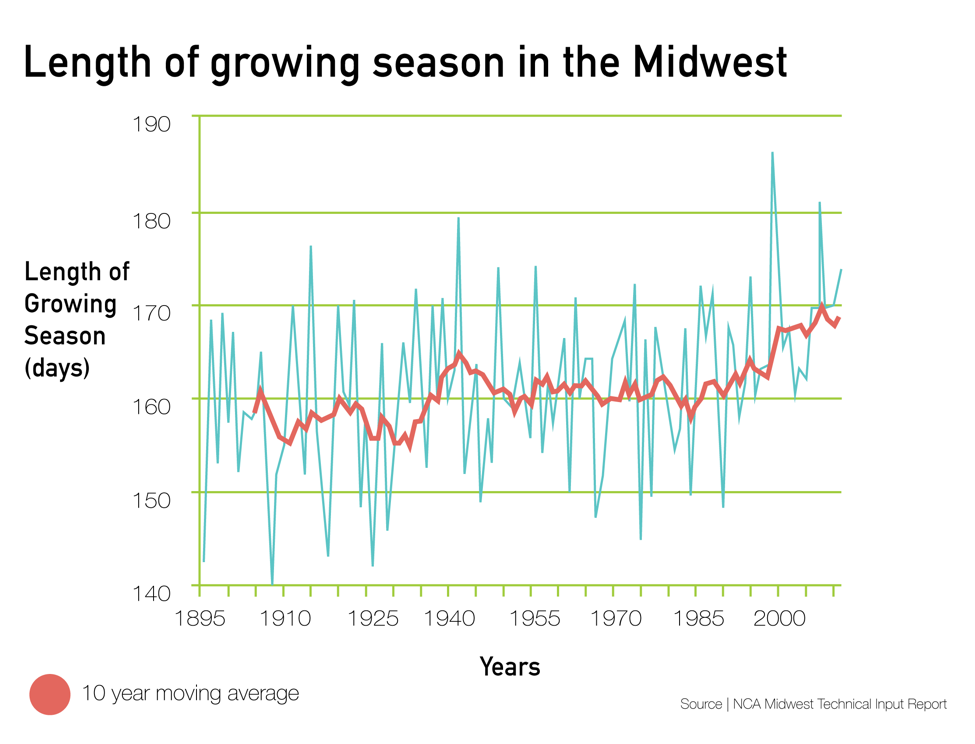

DeVries’ observations are in line with scientific studies, which have found that the Midwest is warming, and that winters are heating up faster than any other season. The growing season has also lengthened by about two weeks since 1950, mostly because of increasingly early springs.

Similar to the Midwest, the Plains states are also experiencing warmer winters. Heavier rain storms during the growing months, particularly in Nebraska and the Dakotas, have become more common. Meanwhile, the southern Plains are projected to get drier and more drought-prone.

A longer growing season can mean more profit for farmers. And Gene Takle, director of the climate science program at Iowa State University, said wetter springs aren’t necessarily a bad thing.

“That’s always what farmers are kind of looking for, to make sure that our deep, water-holding soils are recharged,” he said.

But all that rain can cause problems. “They sometimes come so frequently that there’s not enough time for farmers to get their crop in the ground,” Takle said.

Erratic winter and spring weather creates other headaches, too: frosts that hit right when plants are at their most vulnerable, rainier springs that make planting difficult, and summers that are so dry that nothing survives. In fact, just weeks after DeVries posted, when the winter wheat crop in western Kansas was flowering, the region was hit with a snowstorm.

Takle said that another challenge to agriculture in the Midwest is ever-increasing summer heat, just as DeVries noticed. Recent climate models show that summers in the Midwest are warming faster than any other region in the country. “That’s pretty concerning,” he said.

Tim Thomas, a research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute, whose work combines climate models with crop models to predict climate change’s impact on agricultural yields, warns that hot temperatures could cut yields. Typical corn crops, for example, can’t pollinate when temperatures rise above 93°F.

“Right now in the U.S., our corn belt is sitting right on the threshold of the maximum temperature corn likes, and as the temperature rises another couple degrees Celsius, it’s over that threshold,” Thomas said. “We could see, by 2050, yield reductions of more than 30 percent as a result of climate change.”

A global shock

If crops in the Midwestern U.S. fail on a large scale, the shock will be felt around the globe. But the jolt won’t be felt equally.

“The poorest people in the world will have a harder time as a result of climate change,” Thomas said.

This increase in grain prices may, depending on scale and a number of other factors, make food prices more expensive for consumers. Keith Wiebe, who focuses on the long term agricultural impacts of climate change at the International Food Policy Research Institute, said that higher prices will also lead other farmers in different regions to increase production because they’ll get more money for their crop. That could keep prices on grocery store shelves from increasing too much.

On the other hand, if crops do better than average and yields are up, then grain prices go down and farmers are hit hard. For the farmer, if everyone is overproducing — especially with longer growing seasons — the economic shock can be just as bad as crop loss.

Though a lot of factors in agriculture go into keeping the price of food from swinging too widely, when the scale is big, like it is in the Midwest and Great Plains, there’s a much greater risk that crop failure will have a major impact.

The U.S. is expected to produce 37 percent of the world’s corn exports in the 2016 – 2017 season. “That’s a big chunk, so if there were a real big devastation in the corn belt — let’s say the corn belt for one year had really bad drought — that is going to affect way, way too many places,” Thomas said.

Rising food prices can have major social effects as well. Marc Bellemare, an applied economics professor at the University of Minnesota, has studied this relationship. He compared food price data with news articles about social unrest and found that as prices go up, so do incidents of unrest.

Bellemare’s work also found that the impact of rising food prices is much greater on families in developing countries. In the U.S., he said, people spend between seven and 12 percent of their household budget on food, while in the developing world, people are spending well over 50 percent.

“When food gets more expensive, people in developing countries become food insecure,” Bellemare said: “And people get mad about this.”

What farmers are doing to be more sustainable

Back in Kansas, farmers like Clay Scott, who farms wheat, corn and cattle, are hard at work keeping up with climate change. Scott’s farm uses irrigation water from the Ogallala Aquifer, which has been drying up. So for years, he’s been trying to figure out how to maximize small amounts of water.

On his farm, he’s planted new varieties of corn that require less water, and he’s experimented with irrigation equipment that helps him limit evaporation.

“Over time we’ve adapted and changed our practices,” Scott said. “We maximize that water use to make every drop count.”

It can be hard for some farmers to manage both the day-to-day operations of their farm and keep an eye on future sustainability. But Trevor Ahring, a civil engineer at Kansas Groundwater Management, says he’s noticed a major change in the attitude of farmers toward conservation.

“I do think the culture out here is shifting more towards conserving the water than using it,” Ahring said. “More and more people are realizing their kids might want to farm this land, maybe their grandkids do, and they want to make sure that there’s still something left to farm.”

Fluctuations in agricultural markets have always driven farmers to respond — they’re naturally resilient, and now the market is pushing them to adapt to major environmental changes. And fast.

“Some of those things, you know, conservation groups have been advocating for a longer period of time,” Wiebe said. “But as climate changes, some of those start to make sense for economic reasons for the farmer, too.”

We want to hear from you

Tell us about the impacts changing climates are having on agriculture in your area. Whether you had a conversation about corn with a local farmer or you noticed your tomato plants in your garden doing something unusual, we want to know! Post your sightings on ISeeChange and help us report our next story.

Reported by Samantha Harrington. Produced in partnership with Yale Climate Connections.

Additional cover photos courtesy of David Cornwell, July 20, 2013, Creative Commons.