Residents of Portland, Oregon knew they were in trouble when the sky got so hazy from smoke that the sun turned red. For weeks, people like Michelle Nicola, a Portland middle school teacher, lived enshrouded in smoke from a nearby wildfire.

“It’s like living in the middle of a bonfire,” Nicola said. “You can’t escape it. It feels very oppressive. It’s frightening.”

Great Northern Railway Bridge on the Similkameen River. Looking SE with smoky skies.

At Nicola’s school, kids stay inside for recess when smoke is in the area. The district even cancelled school one day when a wildfire just east of the city, in the Columbia River Gorge, filled the area with smoke and temperatures approached 100°F.

“I worry about everyone with the smoke in the air,” Nicola said. “I feel like once the smoke is in the air we just have to wait for the fire to stop. What actions can we take?”

Breathing Fire Across the US

By the second week of September 2017, there were 39 uncontained large fires in the United States, all burning simultaneously. The vast majority of those fires burned in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho and Montana. The smoke from those fires went everywhere.

Smoke plumes from the Pacific Northwest and Canada’s prairie provinces extended as far south as Mexico and eastward into the Atlantic Ocean.

As a result, millions of people across North America were breathing in smoke.

Health Concerns

According to the USDA, smoke from wildfires is mostly water vapor, but it also contains gases — like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxide — and very small particles called particulate matter that are harmful to human health.

“When you have a wildfire, the level of particulate matter can get really really high,” says Francesca Dominici, a biostatistics professor at Harvard who studies the relationship between air pollution and health.

“Particulate matter are very, very small particles in the air that can penetrate deep into the lungs and initiate inflammation,” she says.

That can cause respiratory and cardiovascular problems. She added that emerging studies hint at a link between air pollution and cognitive health issues.

Recent research has also examined the connection between exposure to air pollution and school performance.

One such study followed nearly 500 children born in Rome in 2003-2004. Scientists determined the amount of air pollution the children were exposed to at birth. Then, when those children were seven years old, researchers administered an IQ test. The results showed that elevated exposure to the pollutant nitrogen dioxide was associated with a 1.4 point lower score in verbal IQ and verbal comprehension IQ.

A similar study looked at the effect of traffic pollution on school-age children. It found that kids who attended ‘highly polluted’ schools in Barcelona had a smaller cognitive development growth than their peers who attended schools in less-polluted areas.

Smoke Alarms

The state of Oregon maintains a “Smoke Blog” that offers an air quality index and tips for how to avoid inhaling too much smoke.

“We’ve had quite a few unhealthy days this year,” said Katherine Benenati, public affairs officer for the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. Her department’s online air quality index crashed a few times this year because there was so much web traffic.

Benenati’s department has about 35 air monitors around the state in high-population areas and near wildfire sites. The department uses information from the monitors to create an index that lets people know when it’s safe to be outside. Air containing an average of 98 micrograms of particulates per cubic meter means the department recommends sensitive groups — kids, elderly residents, pregnant women, and people who have asthma or lung or heart disease– limit their outdoor exposure.

“What we’ve seen this summer is a lot of days in the unhealthy area and even hazardous range,” Benenati said. “That’s where everyone should take precautions, it’s not just if you have lung disease, if you have asthma or you’re elderly.”

But Dominici says staying inside doesn’t guarantee that people are safe.

“It’s tricky for a single individual to protect themselves from fine particulate matter, especially from wildfires, simply because fine particulate matter tends to penetrate indoors as well,” she said. “To protect the community, I think the only way is to prevent these wildfires.”

Which brings us to climate change.

According to the National Climate Assessment, summers in the Pacific Northwest will be hotter and drier than ever before. In fact, summers could see a 30 percent precipitation decrease by the end of the century.

Nicola and other ISeeChangers across the West have already noticed summers getting warmer.

“I don’t even want to go outside,” Nicola said. “It’s too hot, it’s too smoky, it’s not enjoyable to be outside, and that is new.”

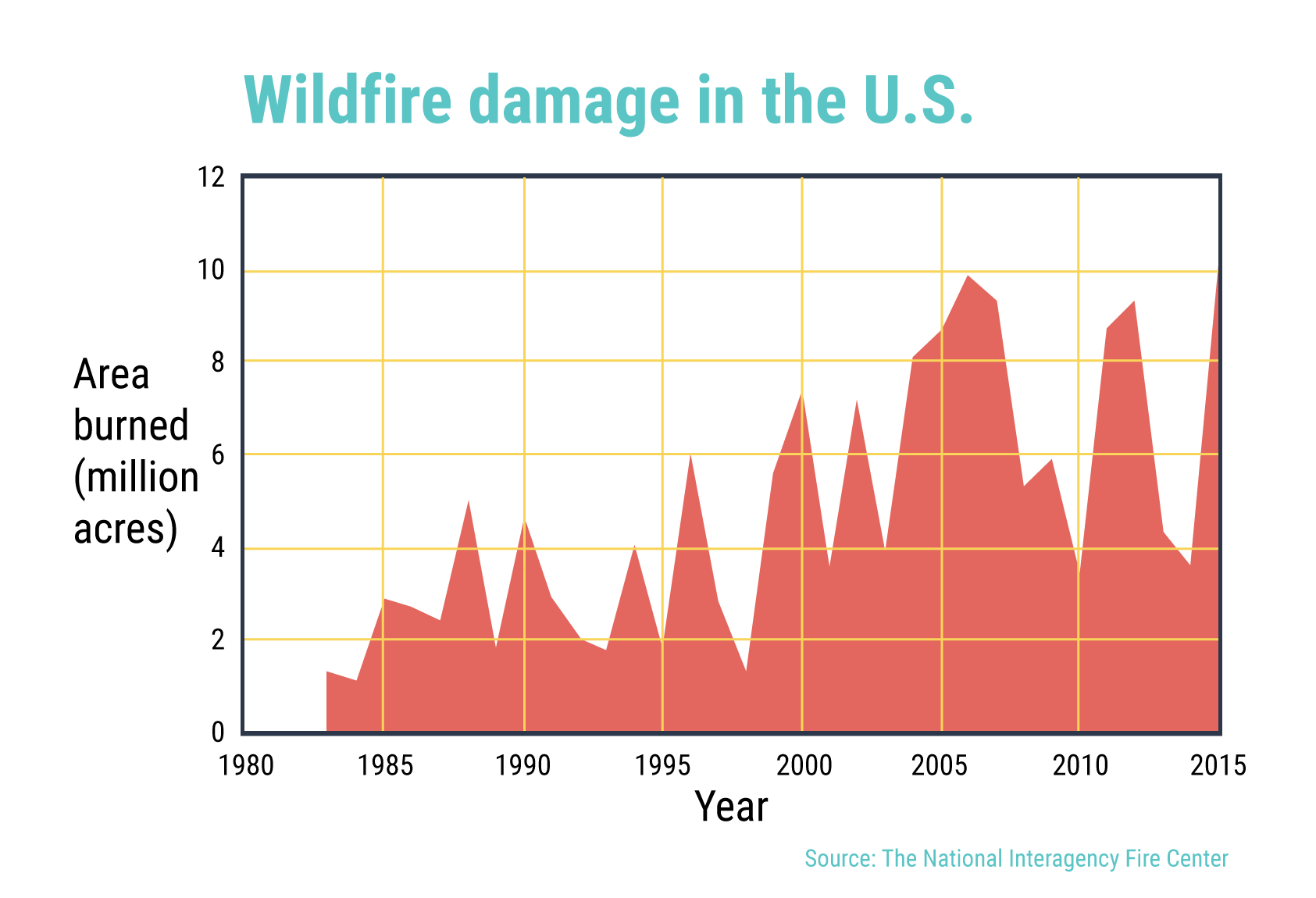

The Northwest has always been dry, which is why wildfires aren’t unusual in the region. But the National Climate Assessment reports that the changing climate has already led to more frequent and bigger fires. It also predicts that the median annual area burned by wildfires in the Northwest will quadruple by the 2080s.

“This year we’re seeing wildfire smoke in places that aren’t as used to seeing it,” Benenati said.

And it’s not just the U.S. In January, Chile experienced wildfires that the country’s president called the worst in Chilean history. This summer, Portugal faced more than 10,000 fires which killed over 64 people. And even Greenland, an island known for its icy terrain, saw wildfires in August.

Wildfire on a hill outside of Ensenada, Mexico. Extreme heat and dry grasses said to be the cause.

Hotter days combined with particulate matter from wildfires are conspiring to contribute to another dangerous health hazard: Ozone, AKA the pollutant in smog.

While wildfires don’t directly produce ozone, studies show that they are a source for ozone ingredients like nitrogen oxide and volatile organic compounds.

A study by researchers at Harvard found that California and the Southwest could see an increase of nine days with dangerous ozone levels under projected climate trends.

Dominici sees fighting climate change and air pollution as killing two birds with one stone. Most air pollution comes from burning, whether it be burning fossil fuels or burning forests.

“The same main sources of climate change are the sources of outdoor air pollution,” Dominici said. “By intervening on climate change it means tackling the sources of outdoor air pollution which means saving lives right now.”

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover art by “Skeeze“/Pixabay and Creative Commons