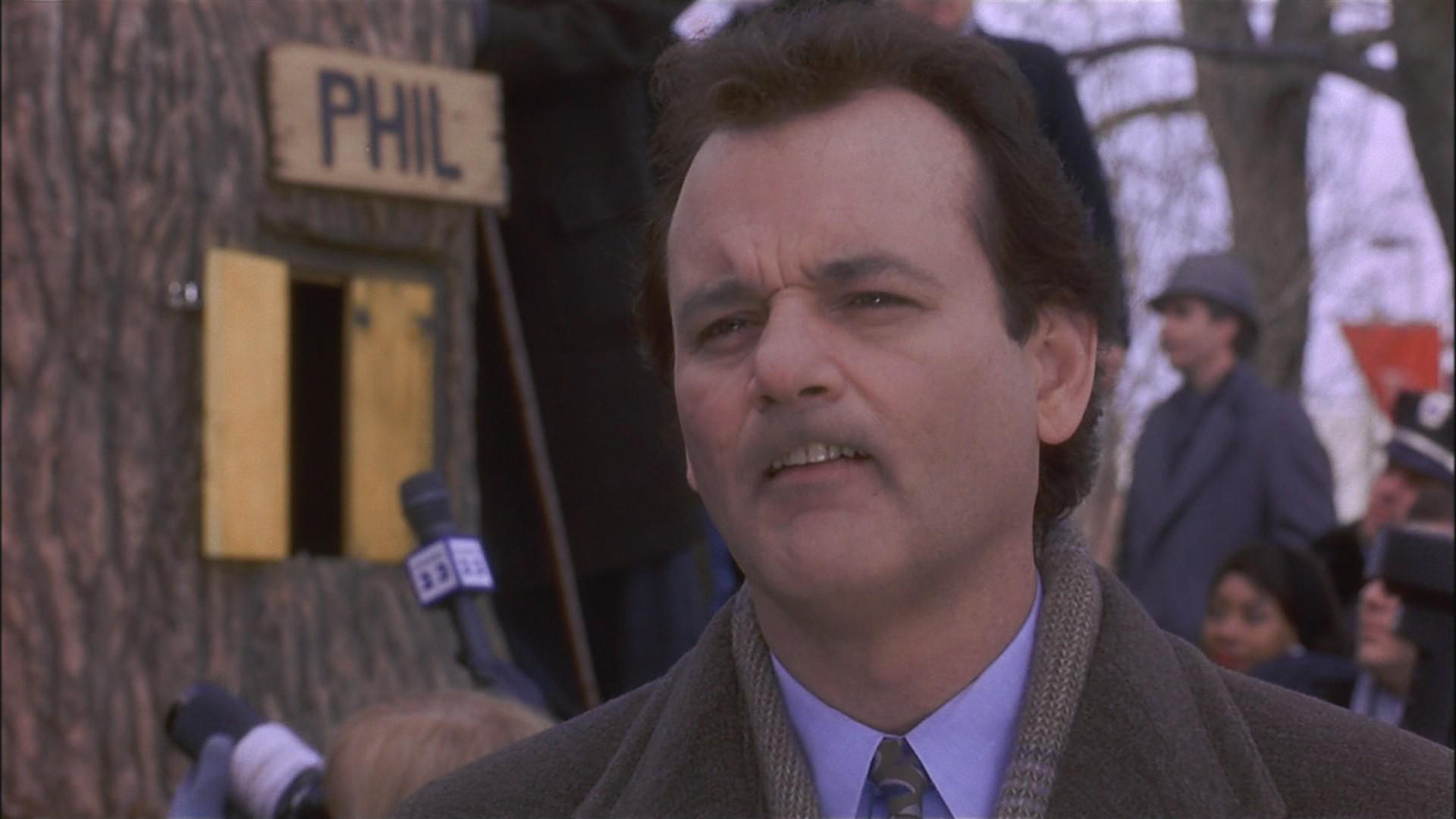

When the Santa Ana winds start gusting in Southern California, the air blows hot and dry and the risk of wildfire skyrockets. But in Tesia Villegas’ neighborhood in Covina, California the wind’s first blast in mid-October was startling and unusual, with trees and branches crashing to the ground.

“One of them was really bad,” Villegas said of a downed tree that fell onto a neighbor’s house. “I actually have never really seen anything like that.”

It was super windy the other day and a couple of trees fell over in my neighborhood!!

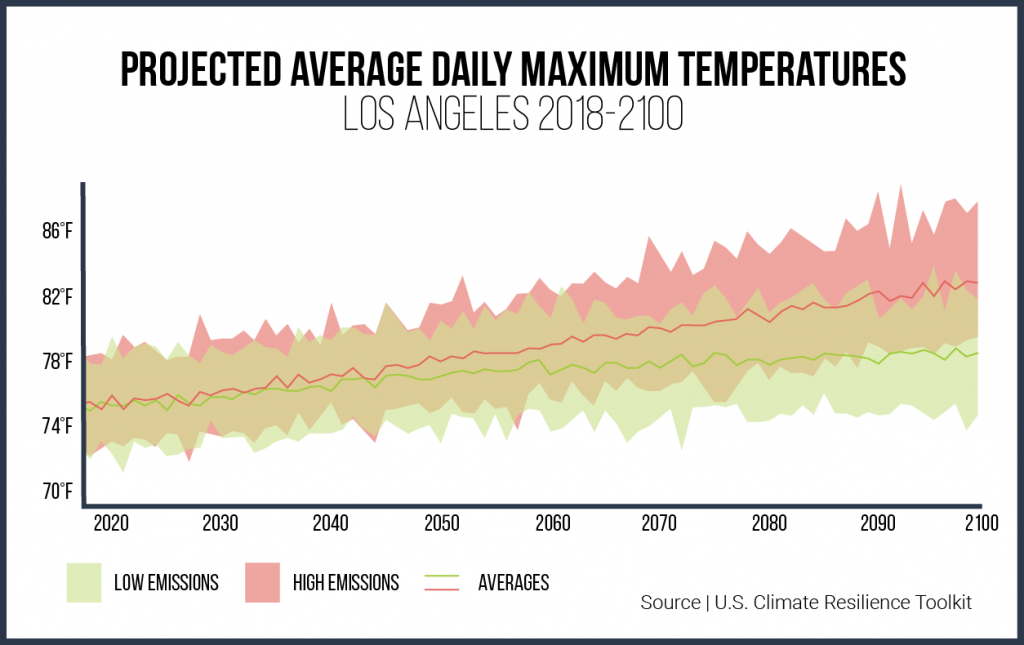

In Los Angeles, Dorrit Ragosine wonders what the impact of rising temperatures will have on the ability of her trees to survive in the future. This summer, leaves on her trees turned crunchy and brown in a heat wave. “I’ve lived here 20 years and, buying the property specifically for the trees, there’s been a lot of changes,” she said.

Serious foliage burn throughtout my neighborhood due to excessive heat.

Natalie van Doorn, a research ecologist with the Forest Service said that many of the trees commonly planted in urban areas in California are temperate species that require a lot of water to survive in hot and dry conditions.

“The concern is very real that the current species that are living in the urban forests are not going to do well in the changing climate,” Van Doorn said.

Parched trees

Looking at Villegas’ observations of wind damage and Ragosine’s scorched leaves, Alison Berry, a professor of plant sciences at the University of California, Davis, said that drought stress was likely a bigger problem than the heat itself.

“Not to say, of course, that high temperature itself could not have negative effects on trees,” she said. “It’s just that water deficit is probably the most damaging environmental condition in our Mediterranean climate.”

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, California has been in a drought since 2011, with many areas getting a brief respite in 2017. The Los Angeles area is currently in a severe drought, and anthropogenic warming is contributing to “warm temperatures, dry soils, precipitation deficits, and low snowpack,” according to California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment.

Drought is also a major concern in the area not just because it dries out urban trees like in Villegas’ neighborhood but because it also leaves the surrounding landscape vulnerable to major wildfires. One month after Villegas’ observation, the Woolsey Fire, the worst wildfire in Los Angeles’ modern history ignited in the grassy hills west of her.

And further inland in Southern California, drought has put the forests of the Sierra Nevada Mountains at risk. A U.S. Department of Agriculture aerial survey found that over 100 million drought-stricken trees died between 2010 and 2016 in the southern and central Sierra Nevada Mountains.

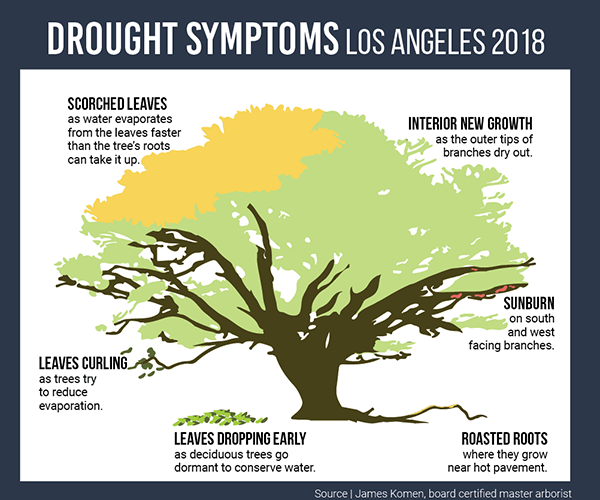

In their work, arborists, or tree doctors, in the Los Angeles area have been seeing increasingly stressed trees. James Komen, a board certified master arborist and the owner of Class One Arboriculture, has seen trees damaged during extreme heat waves.

“On July 6, 2018, we had a record-setting high temperature all across LA,” Komen said. “Many trees could not tolerate the heat, and we are still seeing residual effects from it.”

Adding to the stress, are pests like the pine bark beetle and the shot hole borer, which take advantage of drought-weakened trees said arborist Karina Nordbak at Tree Care LA. The forest service has that the shot hole borer alone could kill 38 percent of native trees in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

Like Berry said, drought remains the underlying concern. Komen said that he has seen signs of drought on leaves, roots and branches.

Adapting forests

Across the U.S., metropolitan areas may lose an average of six percent of their tree species as warming trends continue, according to a 2016 study by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology. At the same time, many municipalities are planting more trees in the hopes of countering extreme heat, controlling flooding and capturing carbon emissions.

To prepare California’s urban forests for climate change, foresters and scientists, including Berry and Van Doorn, joined forces in a project called Climate Ready Trees. The project was started by Greg McPherson, a now-retired research forester with the USDA Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Research Station in Davis, CA. McPherson began thinking about the question of preparing urban forests for drought when he was working at the University of Arizona in Tucson during a drought in the ‘80s.

“Before my eyes it transformed from a city that where there were a lot of grass lawns and a lot of irrigation, to one that was really more of a desert landscape,” McPherson said.

When he moved to Northern California, he began to do mini-experiments with drought tolerant trees to see if any of them would take.

That ultimately led to Climate Ready Trees, a 20 year-study launched in 2014 that spans three climate zones — Northern California’s Central Valley region, a coastal Southern California region, and an interior Southern California region — with a dozen experimental tree species planted in each zone.

The trial species include trees native to drier regions of the U.S. like Arizona, Texas and Oklahoma as well as trees native to islands off the coast of California, and as far away as India and Australia.

Throughout the duration of the study, researchers will regularly score the tree’s ability to handle ten variables including soil conditions, temperature, wind, light and water availability.

Additionally the team is also looking to see if trees can handle a higher level of salinity as they expect more irrigation to happen with recycled water which is saltier. Trees were planted on both reference sites, that have more ideal soil and water conditions, and experimental sites, that are located in parks with varying soil, light and wind conditions.

The Southern California trees were planted only three years ago and the researchers are just beginning to cut off irrigation on the reference sites. As such, Van Doorn said that it’s still too early to know which species they can recommend. But she expects that they will learn more soon. Their trees in Northern California were planted a year earlier and some are already emerging as more or less promising.

Van Doorn acknowledges that the wait for results can be frustrating, and they’ve seen a desire for guidance from both the public and urban foresters.

“They’re always asking, ‘What should we be planting?’” She said. “I feel like the public is now attuned to the fact that we need to make some changes, and they’re ready to make changes, there’s just not enough research, not enough information yet.

Back in Los Angeles, Ragosine is looking for those answers. She has already lost two California black walnut trees, observed wildlife and insect populations declining, and the threat of wildfire hovers in the back of her mind. As winter sets in, she hopes for cooler temperatures and rain to bring drought relief.

“You can’t water your way out of this,” she said. “It’s too hot.”

Show us your trees

How are the trees in your area doing? Show us in ISeeChange posts and track how they grow and change season to season.

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover photo by Photo by Paolo Gamba.