Sure seems like you’re seeing a lot of stressed-out trees, out there in these United States. Unlike with people, it’s probably not because of the impending election.

In the Midwest, observers in Wisconsin and Michigan noticed leaves turning brown deep in what we usually consider summer. Valerie Mann, in Bristol, Wisconsin saw a black walnut turning: “This is a little early,” she said. In Ann Arbor, Michigan, Melissa Hayes saw a yellowing tree August 9.

We’ve gotten similar observations in the Plains states, too. Alexandria Richard in Manhattan, Kansas saw an elm tree’s leaves changing color on September 8.

And up in New England, a group of students from Connecticut is telling us they’re seeing leaves turning in the first week of September, around Hebron, CT, and in Rhode Island.

But it’s not just trees changing color. In Northville, New York, in the southern part of the Adirondack Mountains, Lauren Grupp has spotted all kinds of interesting potential evidence of tree stress, all summer – starting with tent caterpillars on trees around Memorial Day.

She also saw bark beetles on pine trees, and red-humped caterpillars happily chomping away at pear trees.

“What can I do to get rid of them?” she asks. (New York has a few answers.)

So, what should we make of all of these observations? We’re not sure yet. We’d need many, many, many more sightings to be able to say definitively what’s going on in any one of these places. And we’re far from able to connect these events across cities, regions, and states in the absence of more data.

But significantly, this is emblematic of a larger scientific challenge: no comprehensive global monitoring program exists for the world’s forests, and scientists wish there was one. And the trouble with tree health is, it’s influenced by a confluence of forces, each one influenced by climate change in distinct ways. Which means scientists are trying to build a framework for analyzing tree stress out of pieces that are themselves in progress. Some of those pieces of the tree-health puzzle include:

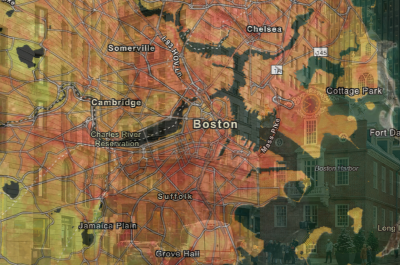

“Hotter drought.” Our observers are seeing dry conditions. Michigan and Wisconsin are abnormally dry in places. New England is in drought, with severe conditions in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York. In the Southeast, severe drought has hit Georgia and Alabama. And it’s not going to surprise you at all that 77% of the West is abnormally dry, with 59% of California in severe, extreme or exceptional drought.

What trees tell us about drought – or don’t – with changing colors and dropping leaves is complicated. Stress isn’t always easy to spot; a tree may work overtime to appear normal. And sometimes, trees will drop half their leaves, or change color, but rebound when they regain access to water.

Large-scale regional monitoring is showing us that hotter drought can have large-scale impacts. Annual tree surveys in California’s Sequoia National Park and nearby Yosemite National Park have found about 2% background mortality in the past. This year, that mortality rate reached 13% among surveyed trees. Nate Stephenson, a research ecologist who works for the US Geological Survey in Sequoia National Park says this die-back is “unprecedented in the instrumental record.”

Scientists suspect climate change is a force multiplier in drought circumstances. “Think of it in terms of supply and demand,” Stephenson says. Historically, drought simply meant lowered water supplies. But now climate change increases what’s know as atmospheric evaporative demand, a measure of overall dryness that sucks moisture out of trees more rapidly. Droughts are bad. Hotter droughts are worse.

Biting beetles in new places. Climate change is enabling pine beetle populations to grow seemingly unchecked. Mountain pine beetles are well-known as hungry predators in the Western U.S., decimating millions of acres of forest unprepared for the onslaught. And southern pine beetles are spreading too, in New England and New York, in part because milder winters aren’t controlling their numbers. (While it did get chilly in Massachusetts during the winter of 2015-16, the cold snap didn’t come early enough or stick around long enough to eradicate the beetles.)

Pine trees and other conifers produce resin that can counter the beetles’ attack. But the mechanisms of resin production – why trees produce it, when they produce it, and what it defends against – are really complicated.

More infestations of defoliating pests, more frequently. Massachusetts saw enormous numbers of gypsy moth caterpillars this summer. The last time it was this bad, in 1981, the caterpillars cut across 200,000 acres of wood. Gypsy caterpillars have been around the state for 150 years, and for much of that time infestations came about once a decade. In recent years, a tree-produced fungus controlled their spread. But in the last two years, it’s been dry, which inhibits the growth of the fungus.

Hotter drought, bark beetles and defoliating pests are phenomena that interact with human interventions – how people manage forests, whether the trees are thinned out or cut away entirely for timber. Not to mention wildfire.

Whatever’s happening isn’t over. And so there’s more you can do to help us document it. Two suggestions:

- More observations in one place. We’re really grateful to the students from Hebron, Connecticut who are watching the trees together. Each individual observation is valuable, and it’s strengthened when people return to the same sites over time, and talk to their neighbors – or in this case, fellow students – about what they see.

- More observations over time. Pest invasions span seasons. You can keep an eye out for caterpillars, and then later, moths. You can return to the same tree over time to provide more data points.

So stay with it; keep an eye on those stressed-out trees – and keep telling us what you see. The more observations you make, the more information and data we have for finding and identifying not only what is going on, but why it’s happening.

(Photo via Flickr, USDA/Anthony R. Ambrose)