Vicky Autrey’s town in eastern North Carolina started off the new year cold and snowy.

A little snow isn’t unheard of in Spring Hope, North Carolina. Autrey said that her town, located 30 miles northeast of Raleigh, can usually expect a few dustings a year. The most recent winter storm brought four inches of snow to her backyard.

But the weirdest thing about this winter this year, Autrey said, isn’t the snow. It’s the cold.

“We’re normally mild. We don’t usually get cold like we had this last time,” Autrey said. “It stayed that way for days and days.”

Persistent cold forced schools in her area to delay start times by two hours, and when Autrey’s granddaughter came over to go sledding, her hair froze.

“I said, ‘You better make sure that you thaw that. Don’t like twist it or you’re going to have a cool haircut,’” Autrey said.

North Carolina wasn’t the only state facing an unusually bitter January. Cold Arctic air has been blowing down across vast areas of the eastern U.S., causing record-breaking low temperatures as far south as Florida.

In the Southeast, state and local infrastructure isn’t set up to handle bitter weather leading to complications like road closures, school cancellations and frozen pipes.

A climate connection?

Although it may seem counter-intuitive, this winter’s extremes are exactly the pattern we should expect with climate change, said Jennifer Francis, a research professor at Rutgers University.

“Rapid Arctic warming is affecting weather patterns farther south,” she said. Francis hypothesizes that winter outbreaks of cold Arctic air are driven by a warming Arctic that is in turn weakening the jet stream.

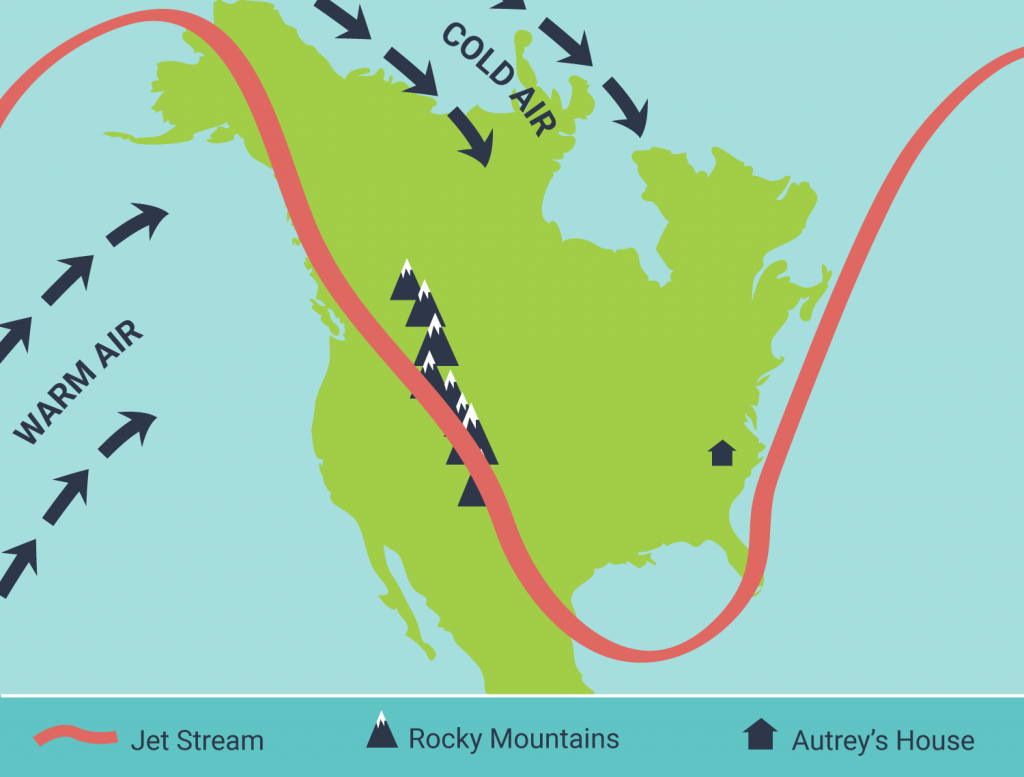

The jet stream, a ribbon of strong wind in the atmosphere, travels along the boundaries between hot and cold air and brings weather with it.

The jet stream gets its energy from differences in temperature. When there’s a large temperature difference between northern and southern areas, the jet stream is strong and tends to flow directly west to east. As the Arctic warms, Francis suspects the reduction in the north-south temperature difference is weakening the jet stream. As a result, the jet stream’s winter flow is getting wavier, allowing cold Arctic air to penetrate farther south.

Francis also suggests that a warming Arctic and thus weaker jet stream are making winter weather stick around longer because the wind pattern of the jet stream gets stuck. In part, she said, that’s because a weaker jet stream is easily deflected by mountain ranges, like the Rocky Mountains, and ocean temperature patterns.

The pattern that has stuck around most of this winter looks almost like a section of a rollercoaster with a big hill over the western part of the U.S. that descends into a valley in the east.

The persistent hill in that roller coaster of the jet stream has kept warm temperatures in the western U.S. like in Alaska where the state broke records for January high temperatures and in Colorado where Amber Kleinman’s bees enjoyed a 50°F day.

In addition to prolonging the amount of time cold weather sticks around, Francis said that this roller coaster-like jet stream pattern also primes the East for snowstorms. This is because storm formation is also driven by temperature differences.

When the valley of the rollercoaster in the east swings back up along the coastal states, it brings cold air from the Arctic and moisture from the Gulf – which is also getting warmer — it meets up with warm air over the ocean, creating a perfect recipe for precipitation.

“Having the ocean extra warm in the western Atlantic,” Francis said, “That provides even more moisture for a storm when it does develop.”

This same dynamic can contribute to prolonged drought conditions in the west. (Check out our radio story from 2012).

But Francis’ theory is not without its challengers. Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said that while the Arctic certainly affects weather patterns, he’s not convinced it plays a major role in the jet stream’s wild swings recently. But warming certainly does:

“I, and many others think the main waviness aspects originate more from the tropics and subtropics,” he said. “The atmospheric effects — in terms of anomalous heating of the atmosphere — are a factor of 10 larger from the tropics, which is also a bigger area.”

While Francis and Trenberth may disagree on the reasons behind it, both have seen that climate change effects winter weather patterns and note that in some cases a warming planet can cause a colder, snowier winter.

“What people need to understand is that climate change is not a problem for their grandchildren,” Francis said. “It’s already happening, and we can see it.”

What are YOU seeing change?

Post your sightings this winter on ISeeChange

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover art by Merkure/Pixabay