The flames still raging in Colorado’s 416 fire are raising questions and increasing concerns as firefighters weigh options ahead in a warming climate.

Heidi Steltzer lives close enough to the 416 Fire blazing through Colorado’s San Juan Mountains that she can see it from her window. “Our house is distant enough to not be at risk of being burned,” she said. But the air outside is smoky and she, and others nearby have been keeping watch on the fire’s growth in the daily news and from reports from neighbors.

The view up the valley from their home is of the whole valley. I watched the fire, the flames, and the smoke as the sunset. The mountains grew dark. The sky grew bright. Helicopters flew water to the fire, thundering as they went nearly overhead. We’ve begun to grow accustomed to their drumming and thumming.

I tried to leave and head home. I tried to stop watching the fire that night. It was mesmerizing. Flames leapt up from the mountain side. I could see the silhouettes of trees. It was the day the fire grew from the back of Hermosa mountain around to the front side, to near many homes.

The 416 Fire sparked on the morning of Friday, June 1 and grew to 2,250 acres that first weekend. As of July 5, the fire was 54,129 acres, 45 percent contained, $28.9 million in cost, and the cause was still unknown.

Steltzer, a biology professor at Fort Lewis College in Durango who studies mountains, knew this fire was serious when she read reports that groves of aspen trees were burning.

“Parts of the landscape, forest types, vegetation types that normally would not be dry enough to full-burn are full-burning” she said.

The situation led Steltzer to wonder if any species and ecosystems were safe from fire anymore.

No-Show Winter of 2018: A wildfire’s dream climate

Steltzer, like others in Colorado, have been documenting extremely dry conditions in Colorado since last November.

Winters with lower-than-average precipitation are expected to become the norm. Climate projections from researchers at the Mountain Studies Institute suggest that the San Juan mountains in the next 20 to 50 years could see a decrease in snowpack between 20 and 60 percent at elevations below 8,200 feet and a decrease of 10 to 20 percent above 8,200 feet.

Julie Korb, a fire ecology professor at Fort Lewis College, says wildfires need three things to burn: Heat, oxygen, and fuel. For a forest fire, dry trees and other plants make an ideal fuel.

“If you don’t have a lot of snow, those larger fuels aren’t going to be absorbing that moisture all winter long, and then when you have an early spring runoff or you have warm temperatures, then those fuels are already starting to dry out,” Korb said.

Studies have connected these periods of drought to climate change. According to a 2016 study by researchers at the University of Idaho and Columbia University, “Anthropogenic climate change accounted for ∼55% of observed increases in fuel aridity from 1979 to 2015 across western US forests.”

The spring precipitation around Durango was never significant, but winters typically stayed cold with snowpack lasting into summer at high elevations, and monsoon rains arriving in early July. Now, winter ends earlier.

There is some snow left but most of it is gone

— AJ White

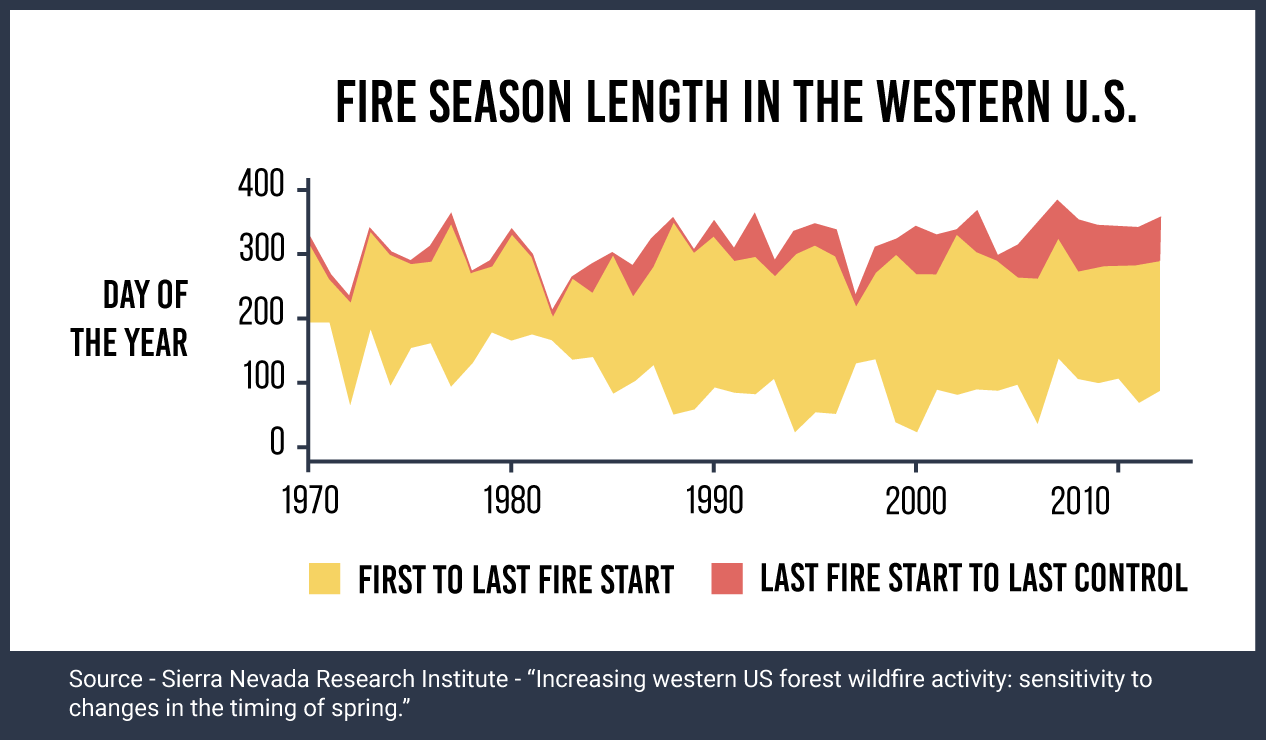

Snowmelt in the San Juans shifted two weeks earlier between 1978 to 2004. This means the gap between snowmelt and summer rain has gotten longer, and with it the risk of wildfire changes.

“The bigger that gap is, the drier everything gets, and the drier the winter is, the drier everything is,” Steltzer said. And the drier the forest, the bigger a wildfire likely will burn.

“Once that ignition happens, then it can move through the forest faster,” Korb said.

The 416 Fire has done just that, and this time it’s taking natural firebreaks into its blaze, which makes the situation riskier for nearby residents.

The aspen are burning

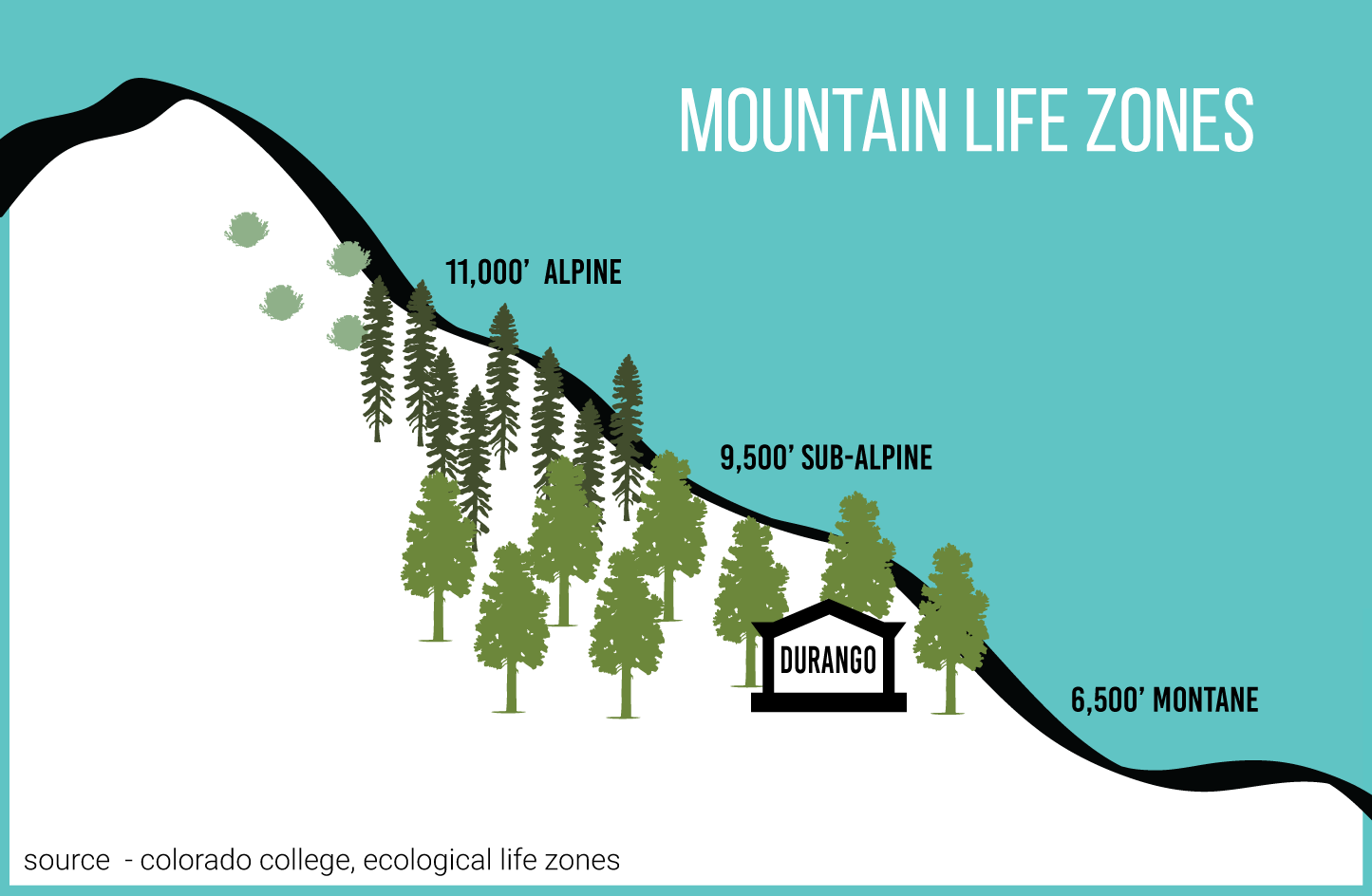

The forests of the San Juan Mountains, at least the ones at montane elevations where most people live, are made up of mostly dry tree species like ponderosa pines, juniper, and other conifers. Mixed in are stands of aspen trees that create pockets of wetter ecosystems.

Because aspens have less acid than pine needles and because aspen stands allow more light to hit the ground and their leaves, the soils around them retain water. Korb said fire fighters may use aspens as a barrier when trying to contain a wildfire. But not this year.

“Essentially what made them barriers no longer exists,” Korb said. “You’re getting these fires moving at a faster rate of spread because it takes less time to dehydrate those fuels to allow them to burn.”

For Steltzer, the burning aspen stands were a sign of the power of the 416 Fire. “I was like, ‘Oh no. This fire’s not going out until July,’” she said.

It also made Steltzer wonder what else is changing this year.

Can the tundra burn too?

Much of Steltzer’s research happens in the alpine tundra, ecosystems at higher elevations above the treeline. Alpine tundra areas in the San Juans rarely burn because, according to Korb, they are typically sparse in fuel, and cool night temperatures bring increasing humidity which makes them wetter in than lower elevations.

But Steltzer said that spring at alpine elevations is changing. Previously snowpack would stick around until the monsoons came. In recent years, Steltzer said, she’s seen snowless alpine areas as early as May.

So, could the new dry period leave room for fires?

Korb thinks it’s unlikely. “It’s not that our alpine landscapes can’t burn, but they really aren’t designed to burn,” she said. “So where we are, I don’t foresee in the future that we have an issue to worry about.”

But people are worrying about tundra fires in Alaska and Greenland, which a 2016 study suggested could see up to a four-fold increase in the probability of fire by 2100.

At high elevations and latitudes, the risk of human-ignited fires is relatively low. But in a study with a global team of researchers, Jim Randerson, a physical sciences professor at the University of California, Irvine, found that the number of lightning-ignited fires has increased around the Arctic tundra since 1975. He said this trend can be expected at lower latitudes too.

“I think for the Rockies that’s a threat– that lightning is going to become an increasing problem at higher elevations,” said Anderson noting good theoretical evidence for increased lightening rates in North America, though it’s still up for debate.

In the San Juans, Korb said that lightning is typically seen only at alpine levels during the monsoons, when things are too wet to start on fire. So she says she’s not concerned about the tundra in her area burning. But, she said she is worried about the region just below it: The subalpine region.

Because the 416 Fire is still burning, Korb hasn’t been able to check whether it’s affected subalpine areas yet, but she suspects it has. Subalpine forests traditionally burn only every 100 to 200 years, but a fire made it to this elevation just 12 years ago.

“For the subalpine, the way that we’re going to see more risks is because we’re going to have more starts happening at lower elevations,” She said. “Because of having more starts, they’re going to be able to move up to those higher elevation forests.”

What does this mean for firefighters?

Doug Fritz, fire chief of Hotchkiss Fire District, three hours north of Durango and 1,180 feet lower in elevation, is already dealing with those increasing fire starts. Bark beetle infestations have killed forests across Colorado; the two most common beetles, mountain pine beetle and the spruce beetle, have impacted 3.4 and 1.78 million acres respectively.

Fritz said that trees that have a high rate of beetle kill fall over faster and easier during wildfires, which makes firefighting more dangerous.

“Fire behavior is more extreme, prompting firefighters to back off even more and rely more on aerial firefighting, and larger air tankers,” he said. “Both techniques are costing lots more money and allowing the fires to get bigger and last longer.”

These troublesome beetles are also more problematic with climate change. According to the National Climate Assessment, warmer winters exacerbate bark beetle outbreaks by allowing beetles that cannot endure harsh cold to survive.

Managing the wildfire cycle amid climate change

Korb feels that better forest management is the best way to prepare Colorado for climate that’s increasingly friendly to wildfires.

For decades government officials and federal forest managers shied away from fire and did everything they could to keep wildfires from igniting. “The first measure necessary for the successful practice of forestry is protection from fire,” Henry Graves, the second chief of the

U.S. Forest Service, declared in 1910.

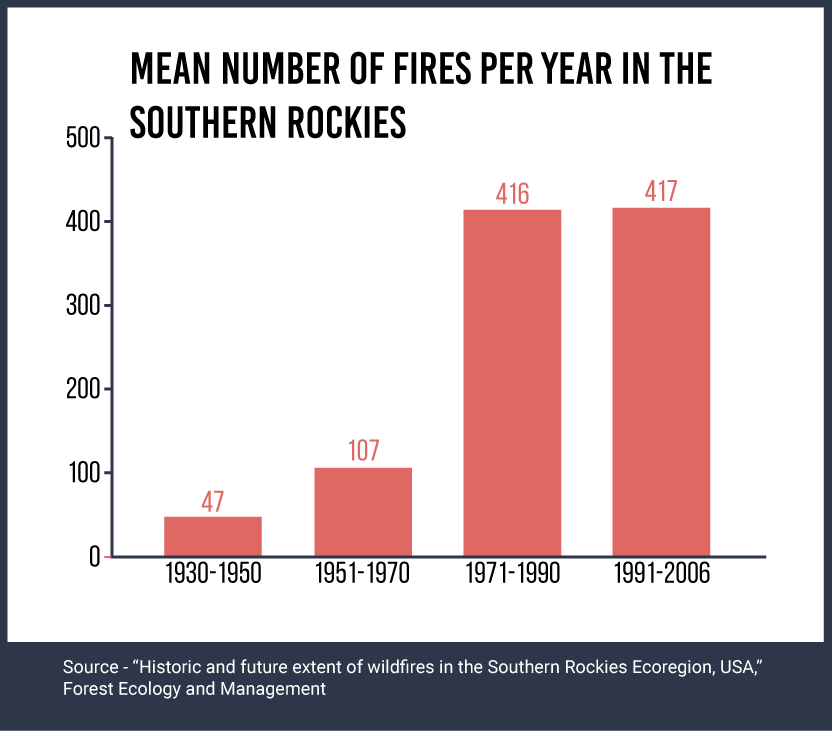

Managing for fire suppression continued on federal lands until the late 1960s.

Current best practices suggest that introducing controlled fires into systems could help prevent larger, wilder wildfires. “You need to put the right type of fire into the forest, but the forest has to be in the conditions in which it evolved,” Korb said.

Dry forests at elevations most heavily populated by humans are the most in need of fire management. The practice of keeping fires out of these areas for so long, Korb said, has enabled shade-loving tree species like Douglas-fir and white fir to grow tall and close together where historically they would have burned just several feet off the ground.

“We’ve allowed fuels to build up,” She said. “So instead of the fire burning on the surface, it’s burning up in the canopy of these trees.”

In her research, Korb has been working on clearing sites of some of that fuel using prescribed burns and cutting to learn how to build more fire-resilient forests.

“We can’t make the snowpack last,” she said. “We have to make these changes on a landscape scale.”

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover photo of the 416 Fire smokeplume by Dom Paulo, Creative Commons.