It took Kathlean Wolf a few extra minutes to get ready. She had to put the braces on her feet that allow her to walk. But once ready to go, she was winding through tall grasses of the marshy stormwater swale across from her apartment on the east side of Madison, Wisconsin. As she walked, Wolf, a certified master naturalist, pointed out edible plants and called out a hello to a butterfly.

Seeing her walking outside in the evening, one might not realize the challenges Wolf and her neighbors face during a heatwave. The community is outside of downtown Madison, home to the University of Wisconsin, so it doesn’t get the extreme impacts of the urban heat island.

There’s a large park across the way from Wolf’s neighborhood, a good collection of shade trees around the buildings, and a breeze coming off nearby Lake Mendota. But Wolf lives in a low-income neighborhood long vulnerable to the whims of weather — from flooding to temperature extremes.

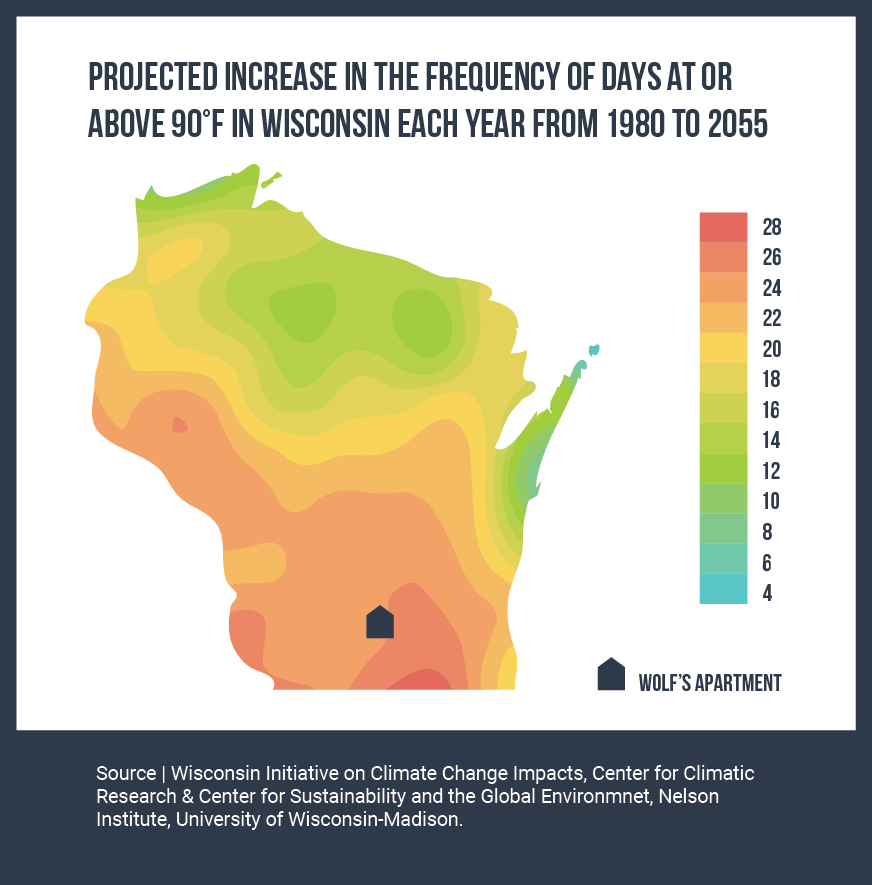

In late July 2019, southern Wisconsin experienced a four-day heatwave with heat index values of more than 100°F. In the middle of that heatwave, Wolf’s apartment — where she lives with her college-student daughter — was 85°F at 2 a.m. She fished ice packs out of the freezer to try to cool down enough to sleep.

My apartment has a single small AC wall unit in the living room. Running this unit is the #1 expense for utilities all year long. Box-fans on the floor blow toward our bedrooms, and I mounted window-fans at the top of doorways to help push hot air back toward the AC unit. This usually circulates enough cool air back to my bedroom to keep it below 80 degrees.

I use night-time cooling religiously; the instant it’s cooler outside than inside, open up the windows and doors, run fans to draw in cold and blow out heat. Then close things up the instant it’s warmer outside than in. But nights have been too hot for this to work like it usually does–heat’s building up in the apartment and the attic above.

Last night, it never got cool enough to open the doors and windows. With the heat slowly creeping down from the attic, it rose to 85 degrees in my bedroom by 2 a.m., and it was still 88F outside. I finally grabbed a large ice-pack from the freezer, put it under my chest, and cooled down enough to sleep.

It’s depressing to think that this will be our future. I have a disability, and I’m really hurting today because I couldn’t sleep last night. How can I possibly stand it if there are long weeks of this every year in coming years? For someone who’s disabled, poverty doesn’t tend to get better–it gets worse, and my housing situation could get worse, my access to AC will end, and I’m not going to live through that.

Also, here is a picture of the frogs my daughter rescued from the window-wells of our building (they get stuck there and die), just before she took them over to the creek and set them free. Heat is depressing; a daughter carrying five frogs in her shirt, that makes me happy!

For anyone, that’s an uncomfortable night. For others, it’s unsafe as overnight heat prevents the body from getting a much needed cool-down. Climate change disproportionately threatens the health of vulnerable groups. According to the 2016 Climate and Health Assessment, vulnerable groups include: “those with low income, some communities of color, immigrant groups (including those with limited English proficiency), Indigenous peoples, children and pregnant women, older adults, vulnerable occupational groups, persons with disabilities, and persons with preexisting or chronic medical conditions.”

For Wolf, who lives with a physical disability affecting her joints and also bipolar disorder, the heat left her lacking energy.

“There’s a point at which, you know, if I had to put up with too much heat, that could physically kill me, or it could just make life so not worth living,” Wolf said. “I think that’s the biggest way that heat, disability affects me, is the only way I keep my bipolar level and steady is, besides the medication, I have to go out in the woods. I have to go out in the marsh. I have to go out in nature.”

Wolf, who regularly leads educational programs around the nearby park, said that if the heat prevents her from getting outside, life would be unbearable. “I’m not equipped for that,” she said.

Climate change is hard on people with disabilities

According to the CDC, one in four American adults, or 61 million people, live with a disability. For many, high temperatures can be a major challenge. Alex Ghenis, a policy and research specialist at the World Institute on Disability, manages New Earth Disability, a project which addresses the ways that climate change affects people with disabilities.

There are physical effects for some. Ghenis, for example, has a spinal cord injury that inhibits him from sweating, the body’s primary way of minimizing overheating. Additionally, there are social aspects, like being more likely to live in poverty, having a harder time accessing transportation, and being more likely to be socially isolated than able-bodied people.

“Climate change — and natural disasters in general — threatens the stability of the built environment, that accessible built environment that supports independent living,” Ghenis said, “Any single disastrous event can throw that out of whack and really endanger people with disabilities.”

Wolf’s apartment has one window air conditioning unit in the living room, and she’s rigged a series of fans to try to get more air circulating. “I have box fans that are on the top of the doorways that blow hot air back to the living room where the A/C unit is, and then four box fans that blow it back towards the back,” she said.

But it’s rare that she runs her A/C too much. “As an environmentalist, I can’t bring myself to do that,” she said, “I also can’t afford it. I add my bills up right now and it’s like, ‘Oh my bills exceed my available income.’”

Poverty makes people more vulnerable to weather extremes

Wolf’s neighborhood is one of the few affordable spots (“If $825 a month is affordable,” Wolf said) left in the increasingly sprawling metro area.

According to the city of Madison’s Neighborhood Indicators Project, median household income in Wolf’s area trails that in the city overall by more than $13,000. Additionally, the unemployment rate in Wolf’s area is 10.2%; in the city as a whole, it’s 4.1%.

“For low-income and vulnerable groups, they’re typically in the poorest housing conditions,” said Jenna Tilt, an associate professor at Oregon State University who teaches geography, environmental sciences, and marine resource management and often works with emergency planners on best practices.

Low-income communities are more likely to find affordable housing in flood plains or in older or cheaply built buildings that may not be equipped to handle temperature extremes. Additionally, they are more-likely to have jobs that require them to work through the heat.

There has been some effort to shore up vulnerabilities in Wolf’s area. When she first moved in, in 2013, flooding was a major issue. In the past, the street in front of her apartment building flooded regularly as stormwater raced down a concrete channel into nearby Lake Mendota.

During one storm, the water was so deep that Wolf and her daughter kayaked up and down the street, and in another, floodwaters destroyed Wolf’s car. After the concrete ditch was replaced with native plants and and a more pond-like system, flooding has been much less of an issue.

Additionally, earlier this year, a local non-profit called Project Home installed new insulation in the attic of her building to help bring some relief from both hot and cold days.

“How much worse would it have been if there hadn’t been as much insulation in the attic, I don’t know,” Wolf said.

When emergencies hit

In Dane County, where Madison is located, emergency managers are having to put more resources into heat-related planning. John McLellan works with the county’s department of emergency management as a population protection planner.

“In terms of the amount of staff time our office is doing to ensure we’re being vigilant and we can stay ahead of the curve, yeah we’re spending a lot more time doing that,” he said. “Whether you attribute it to climate change or not, we’re spending a lot more time doing these things than we were five, 10 years ago.”

During heatwaves, McLellan’s office coordinates with area service providers to ensure that there are available places people can go to get cool — libraries, for example, are cooling centers which Wolf has taken advantage of — and transportation to get people there.

Cooling centers aren’t open overnight, when heat can be especially dangerous for people without A/C, and overnight shelters are rarely set up during heat waves in Wolf’s area. McLellan said that the county had never opened an overnight shelter for heat and that the City of Madison had only done so once.

The county primarily relies on broadcast news to provide notifications about risks and resources, but McLellan acknowledges that approach is not perfect — particularly, he noted, as people leave traditional broadcast media sources, like local TV and radio stations, for streaming services. So his team is also active on social media, like Facebook and Twitter.

Additionally, McLellan said they try to reach particularly vulnerable populations through organizations that work within those communities like homeless shelters and libraries, and their listservs.

Wolf is pretty plugged in, but she still wasn’t totally sure what resources were available during that heatwave. “The disability resource center over there,” she said, while pointing down the street, ”seems like that’s a really good outreach point, but I’ve never heard a word from them.”

Ghenis said it would be helpful for those providing risk warnings to do so specifically for the disability community to also provide advance information about when the power grid may be at risk of being overwhelmed and information about accessible shelters.

Sudden downpour = gravel on the sidewalk. Concerned for wheelchair users.

Tilt, the Oregon State professor, acknowledged that preparing for climate change requires dedicating more resources to emergency planning and managing.

“All those things take money. It can be a huge constraint, but I think we have to start thinking about it as an opportunity,” she said. “The cost of doing nothing is not zero, right, in terms of health, in terms of community well-being, and who’s suffering.”

The need for communities to build resilience before an emergency

Tilt said that planning for climate change on a more long-term scale can ease some of the burden when an emergency does happen. For dangerous heat waves, that can mean planting more trees to reduce urban heat, ensuring that affordable housing is built to standards that keep some of the heat out, and installing air conditioning when necessary.

“These are larger systemic issues in terms of planning that have to be addressed or we’re always playing catch up,” she said. “That’s a really important thing that we have to start moving the needle towards with climate change and adaptation — that we’re really thinking about everything from our transportation planning, our housing policies, our land use policies.”

Tilt said that integrating community leaders into the planning process and leaning on their expertise is also important. She said that it’s best to reach people where they already are – where they work, where they worship, and where their kids go to school. Ghenis echoed this point and said it’s critical that people with disabilities be involved in developing emergency plans.

Beyond official plans, individuals can also work to build connections to help their community withstand emergencies better. Ghenis said that establishing relationships with neighbors before someone needs to ask for help can be invaluable.

“Any sort of people doing more to get to know their neighbors, to understand what needs are, to build networks of mutual support and communication,” Ghenis said. “I think people with disabilities being OK with asking for help and viewing that as a normal part of life, instead of admitting some excess level of vulnerability and feeling shame around that, is important. And then on the flip side, able-bodied folks that are helping out to just accept it as a neighbor who might need a hand, as opposed to a burden on them or some societal duty.”

In her community, Wolf works to build that neighbor-to-neighbor connection. She says hello to those who pass by — humans and animals alike — and just added two blueberry bushes she found on discount to the community garden she tends behind the building.

“I don’t worry about me so much,” she said. “It’s other people.”

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections.

Cover photo – portrait of Kathlean Wolf via Samantha Harrington.