Constanza Porche, a bus driver for Tulane University, travels all over town. On August 5, 2017 at one point along her route uptown, it started raining and Porche soon began to see water spouting out of the manholes on the street. Some streets stayed clear of water while others were quickly submerged.

“We flooded and we couldn’t understand why,” Porche said at a storytelling event co-hosted by ISeeChange and Bring Your Own stories in MidCity, one of the most flooded areas of the city last summer.

At the end of her workday, Porche rushed home to Gentilly to check in on her 14-year-old son. She weaved through neighborhoods, searching for safe, drivable streets. A trip that normally takes 15 minutes, took her two hours. When she got home, Porche – having weathered Katrina- was certain the floodwaters would soon reach her home, so she started to prepare. She brought out the suitcase she kept her photos in case she needed to carry them to higher ground.

Porche said that all she wants is to be able to feel safe without keeping her memories stowed away. “I have to put my life in a suitcase because we have a failed pumping system here in New Orleans.”

Because much of the city is below sea level, New Orleanians are no strangers to flooding. There’s no natural drainage point for water that floods the city. Instead it all must go into a storm drain, then through the pipes below city streets and into a pumping station which directs the water to something called an “outfall canal” which carries the water to Lake Pontchartrain.

“There’s no metropolitan place, no metropolitan city, in the world that has a drainage system that even comes close to what the Sewerage and Water Board has for the city of New Orleans,” Joe Becker, the former general superintendent of the board, said during the same MidCity storytelling event.

Just a reminder we are still alive.. does our city know we have drainage issues? {sarcasm}

But even long-time residents have noticed that things seemed to be getting worse with storm water. In early spring 2017, ISeeChangers from New Orleans were posting their concerns about flooding streets. Just a few months later, the city would begin a cycle of flooding and finger pointing-that continued throughout the summer.

After the August 5 storm, the New Orleans City Council blamed the Sewerage and Water Board for mismanaging the flooding which led to the ousting of the board’s general superintendent, Joe Becker. But, as this story will explore, the pumping system – though fraught with significant issues – didn’t fail as badly as many thought.

So what changed?

What has made flooding in New Orleans so much worse? Although many residents blame broken pumps or outdated drainage infrastructure, ISeeChange community data alongside reports from the National Weather Service suggest that it would take a lot more than a perfectly-running pumping system to keep New Orleans’ streets dry.

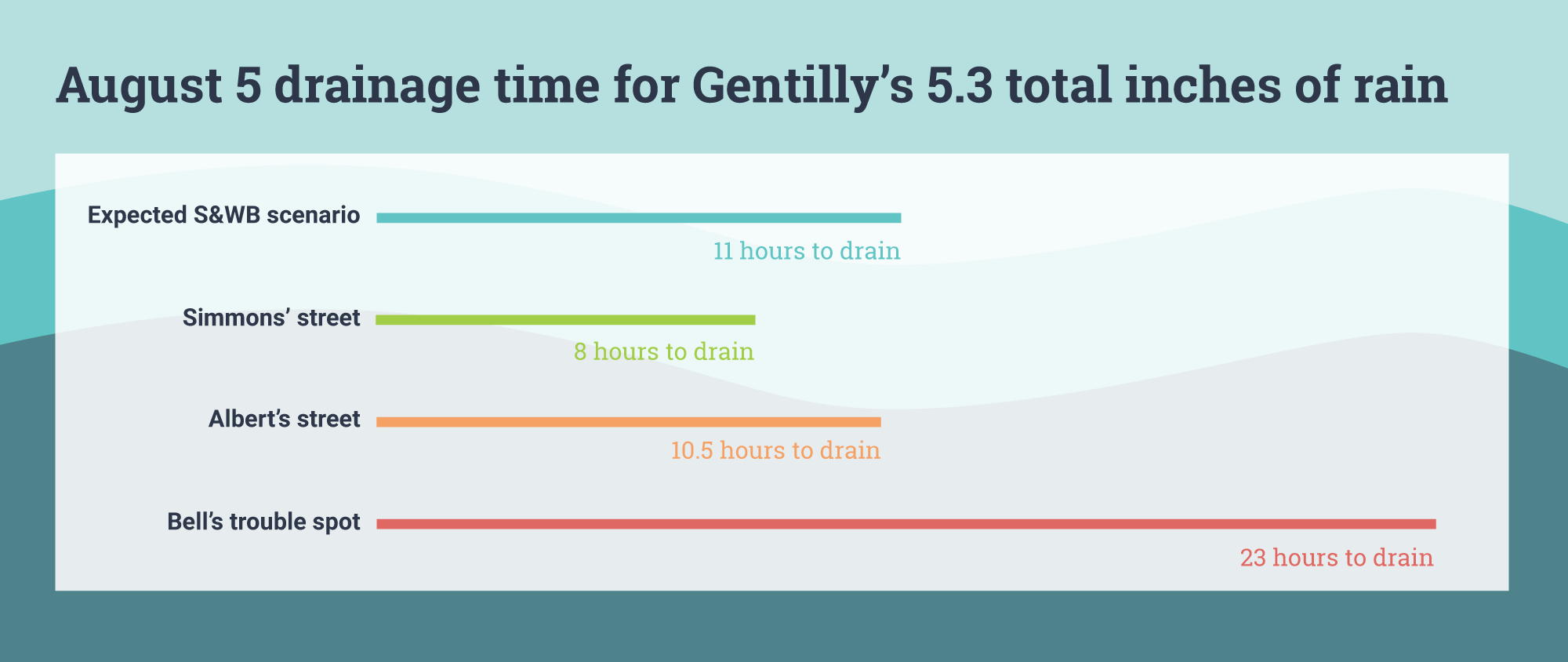

Kate Simmons said that she knows when the pumps are doing their job to drain her street because she can see and hear moving water. “There were no bubbles until 11:42 PM,” she said of August 5.

Simmons said her street was completely drained by 12:15 AM on August 6. Allison Albert, another Gentilly ISeeChanger half a mile away from Simmons, was up until the early hours on August 6, and noticed her street was draining at 3AM.

For Simmons, the rain event itself didn’t feel abnormal, but the resulting flood did. “I ended up at the urgent care the next day because I had a gash in my hand, broke my toe and sprained my knee falling in the floodwater walking to my house,” she said.

Porche also thought the rain event was routine. “We just had a little bit of rain, nothing that should have been major,” she said.

What the data said

Rain gauge data told a different story. The storm was small but intense. Some neighborhoods got upwards of nine inches while the airport – where official gauges are kept – registered no rainfall at all. MidCity experienced a 100-year-rain event, meaning there’s a 1% of getting such a storm once a year. In Gentilly, it was a 25-year event, meaning there’s a 4% chance of that kind of storm happening once a year.

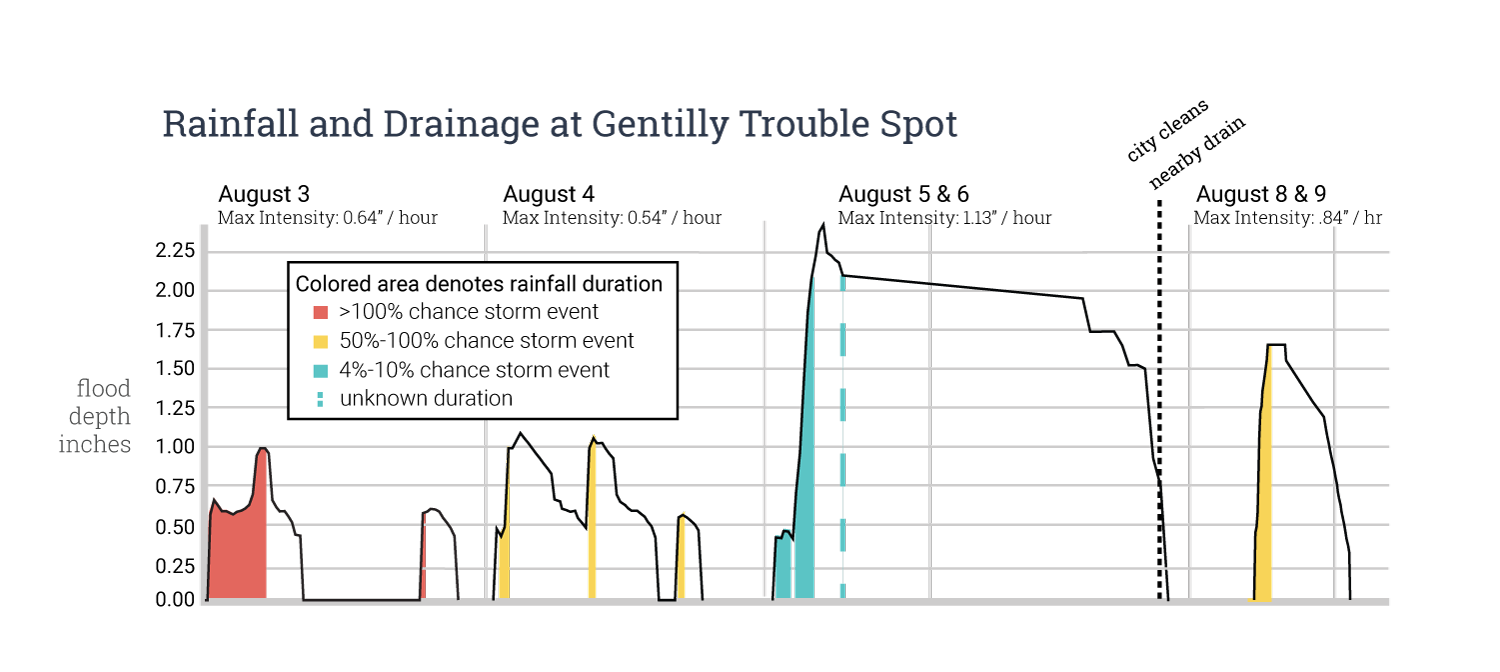

Throughout the summer, ISeeChange asked residents to document flooding in their neighborhoods. ISeeChange also deployed rain gauges and field cameras to document rainfalls as well as high water marks in a Gentilly neighborhood trouble spot. On August 5, that spot received 4.3 inches of rain between 3:22 and 4:22 PM, and then another inch that night. Another rain gauge in the neighborhood demonstrated similar totals.

The Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans expects the pumping system to be able to drain one inch in the first hour of rainfall and half an inch every hour after that. When the rain comes faster than that, it doesn’t matter how well the pumps are working. Streets will flood regardless.

Scott Lincoln, a hydrologist and cartographer for the National Weather Service, came to a similar conclusion in a report on the August 5th storm that, “the heaviest rainfall occurred over a roughly 3-hour period, and this accounted for at least 80 percent of the storm total.” Additionally, he estimated that the total rainfall was about 1.5 times the pumping capacity.

At the city council meeting on August 8 after the storm, city officials noted 14 pumps were not operating during the event. Though this left the system at less than 100% capacity, Lincoln’s report suggested that flooding may have occurred regardless. His findings show that rainfall rates during the August storm exceeded the city’s assumed pumping capacity.

The impact of climate change

So it’s not so much the pumps, rather it’s the storms themselves that have changed. Rising temperatures in the Gulf — 2017 was the first time daily surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico never dipped below 73°F — conspire to make rain storms more frequent and more intense. The warmer Gulf helped fuel both hurricane and storm flooding events in the Southeast with billion dollar price tags, among them Hurricane Harvey -the largest single rain event in the continental United States.

According to the National Climate Assessment, the Southeast has seen a 27 percent increase in heavy precipitation events from 1958 to 2012. Climate models predict that the intensity of rainstorms will only increase as the years go by.

So why didn’t residents know this rainstorm was different? Sometimes the increased intensity of specific storms gets lost on radar–particularly typical summer afternoon rainstorms in New Orleans. On August 5, forecasters told residents to prepare for a few inches of rain. By analyzing rain gauge data, ISeeChange and Scott Lincoln separately found that radar rainfall estimates were too low for most areas of the city. The areas that received the most rainfall during that particular storm saw almost double the amount of rain than what the radar reported.

Another factor during the August 5, 2017 storm were rainstorms that caused flooding two days prior: Though the storms on August 3 and 4 were smaller and less intense, they helped to saturate the soil and system, creating even less space for the August 5 rain to drain. More frequent rain events are also a projected impact of climate change and will incur more wear and tear on the drainage system over time.

When residents become experts

Back at ISeeChange’s Gentilly monitoring site, over 30 cars were stranded in the grassy median near the intersection while the street took over 23 hours to drain on August 5 and 6. On the city’s flood maps, this intersection does not stand out, but the team was able to identify it as a trouble spot thanks to reporting from ISeeChangers.

Back at ISeeChange’s Gentilly monitoring site, over 30 cars were stranded in the grassy median near the intersection while the street took over 23 hours to drain on August 5 and 6. On the city’s flood maps, this intersection does not stand out, but the team was able to identify it as a trouble spot thanks to reporting from ISeeChangers.

As the city works to respond to the challenges posed by more intense storms, neighborhood residents are best equipped to provide local perspectives of trouble spots and to verify the accuracy of flood models.

Monitoring these hot spots can help the city, the National Weather Service, and green infrastructure designers plan for increasingly major flooding events.

The Gentilly neighborhood is a pilot for green infrastructure projects that can store some excess storm water and relieve some of the strain on the pumps.

However, solutions to New Orleans’ drainage problems need to be more comprehensive than just one neighborhood experiment. Stormwater is every resident’s problem because every neighborhood and every block experiences it differently.

Updating the entire system would cost an exorbitant sum. A recent federally funded drainage project in the Uptown areas of New Orleans cost $700 million dollars. “That bought me about a half inch of rain storage capacity,” said Becker. “That’s how expensive drainage is.”

Though the conversations about drainage in New Orleans are complicated, they are ones that residents want to have. The storytelling event that Porche and Becker attended had a large turnout of concerned citizens ready to help their neighbors in whatever way they can.

“People would spend the time to have those discussions,” Simmons said.

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover art by Fernando Lopez/Creative Commons

In 2018, ISeeChange is expanding its rain gauge and citizen led flood monitoring work across New Orleans. If you want to monitor a flooding hot spot with us, post pictures of flooding on ISeeChange and request a rain gauge! Stay tuned for more ISeeChange conversations and events near you.

Previous New Orleans flooding stories:

- Can A Saltier Sea Predict Spring and Summer Floods in the Gulf South and Midwest?

- Yes. Your streets are flooding more.

Correction: A previous version of this story quoted Lincoln’s report as saying that during the August 2017 event, “Even a significant reduction in pumping capacity would have had minimal impact on the resulting excess flow.” In that quote, the report was referring to a 1995 flood event.