High on a hill above the village of Cross Plains, Wisconsin the rain came down in sheets against the windows of the house where I was staying. As I listened to the wind thrash tree branches, I’d never been more grateful to be on high ground. After a few hours of heavy rain, the power went out. I kept tabs on social media as flash flooding devastated the town below me.

Between the afternoon of August 20 and the next morning, 14.7 inches of rain fell on Cross Plains. Homes, businesses, bridges and parks were washed out along streets, rivers and ponds. It took six days for the main highway out of town to reopen.

The August 20 event in Cross Plains and western Dane County was deemed a 1-in-1000 year event, which means that a rainstorm of that magnitude historically has a 0.1 percent chance of occurring each year.

But we didn’t get a break anytime soon. Unrelenting storms rolled through southern Wisconsin for three weeks. There were more flash floods, and river flooding spread across the area. According to the National Weather Service, an unusually high level of moisture in the atmosphere was to blame for all of the heavy rain.

Wisconsin isn’t the only place getting wetter

Intensifying rainfall is a well-documented climate change trend. Across the country, local governments are making infrastructure investments in the hopes of preparing for more water.

But planning for stormwater is challenging when the rainfall probabilities that planners and engineers once relied on to design infrastructure are no longer accurate. Wisconsin, for example, experienced historic flooding in 2008, 2013, and 2016, in addition to 2018. Probabilities based on long-term averages don’t necessarily capture what can be expected from future — or even current — storms.

Dane County Executive Joe Parisi said my county has been preparing for more intense storms since at least 2011, when researchers from the University of Wisconsin released the first Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts report.

“It was a wakeup call back then,” said Dave Merritt, director of policy and program development for the Dane County Department of Administration. “But there’s nothing like experiencing the real thing.”

Updating the stormwater math

When planning to control rainfall runoff, engineers rely on “design storms” to give them an idea of how often their area can expect a certain rainfall intensity. One of the most well-known methods of establishing a design storm is using probabilities based on historical averages.

But with climate change increasing the probability of intense rain events, these design storms are less accurate. “The standards that the engineers require or need don’t currently exist,” said Joe DeAngelis, a researcher at the American Planning Association’s Hazards Planning Center.

Angeline Pendergrass is a project scientist at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. She said scientists should be able to correct recurrence intervals to make them more accurate. This could be done by simulating what past storms may have looked like with future climate conditions and analyzing past storms to identify how climate change affected them.

“We can say something about what component of changes in precipitation and storms in the past we think is due to changes in climate versus the parts of it that are just due to natural variability,” Pendergrass said. “That’s the kind of information that we would need to combine with existing historical records.”

A partnership in New York is already creating new projections. The Northeast Regional Climate Center, Cornell University and the state worked together to develop a tool that shows the probabilities of different rain intensities across the state as far into the future as 2099.

This kind of collaboration between officials and scientists is key. DeAngelis pointed out that regional climate centers can help local governments away from big cities or in unsupportive states scale down climate models to get a more detailed understanding about future rain intensity for their area.

Some level of uncertainty will always exist because every storm is affected by a multitude of factors, from air flow to topography. Nicholas Rajkovich, an assistant professor of architecture and the leader of the Resilient Buildings Lab at the University of Buffalo, said that can’t be used as an excuse to not prepare.

“This can be a place where people don’t take action because they want to see the perfect data,” he said. “We might not know what the exact rainfall rate is going to be in the future, but we know it’s probably going to be a lot larger and a lot more intense, so if we’re moving systems in a direction to be able to deal with that, it might not be a hundred percent perfect in the future, but it’s well on its way.”

In Dane County, decision-makers believe the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts report provides enough data to have a good idea of what is needed for now. For example, the report suggests that 100-year rain storms in Wisconsin can be expected to be 11 percent more intense by mid-century. That means that if a location currently has a 1-in-100 (or 1 percent) probability of receiving five inches of rain in 12 hours, by 2050 they may have a 1 percent chance of getting 5.55 inches of rain in 12 hours.

What is needed, officials said, is a more comprehensive approach to storing and slowing stormwater as well as identifying and responding to “choke points” like excessive aquatic weeds and bridges that stall water as it moves out of the chain of lakes in the county’s center.

Madison, the Dane County seat and state capital, sits between two lakes connected by a river. Stormwater from the August 20 rain event caused street flooding along the lakeshores and the area where the river cuts through the city. Subsequent public debate centered around combating future flooding by lowering lake levels. But county officials worry that the attention on lake levels takes focus away from the need to capture and slow stormwater before it even gets to the lakes. Lower lake levels may have alleviated some of the lakeshore flooding and is something that the county may ultimately aim for. But more room in the lakes wouldn’t have prevented the more damaging flash floods or river flooding in other watersheds in the county.

“Do you either adapt or do you mitigate?” said John Reimer, deputy director of the county’s Land and Water Resources Department. “We can change the lake levels and adapt, but you probably still have it happen, or do we actually mitigate on the land?”

In pursuit of lessening the impacts of more intense storms, the county will work with local municipalities to build their stormwater retention capacity, so that less water flows into the lakes all at once. They also hope to increase funding for wetland and prairie restoration projects. For example, a new program that Parisi’s office proposed for 2019 would pay agricultural landowners to replace fields with native grasses that can absorb stormwater.

More green infrastructure is popping up in big cities

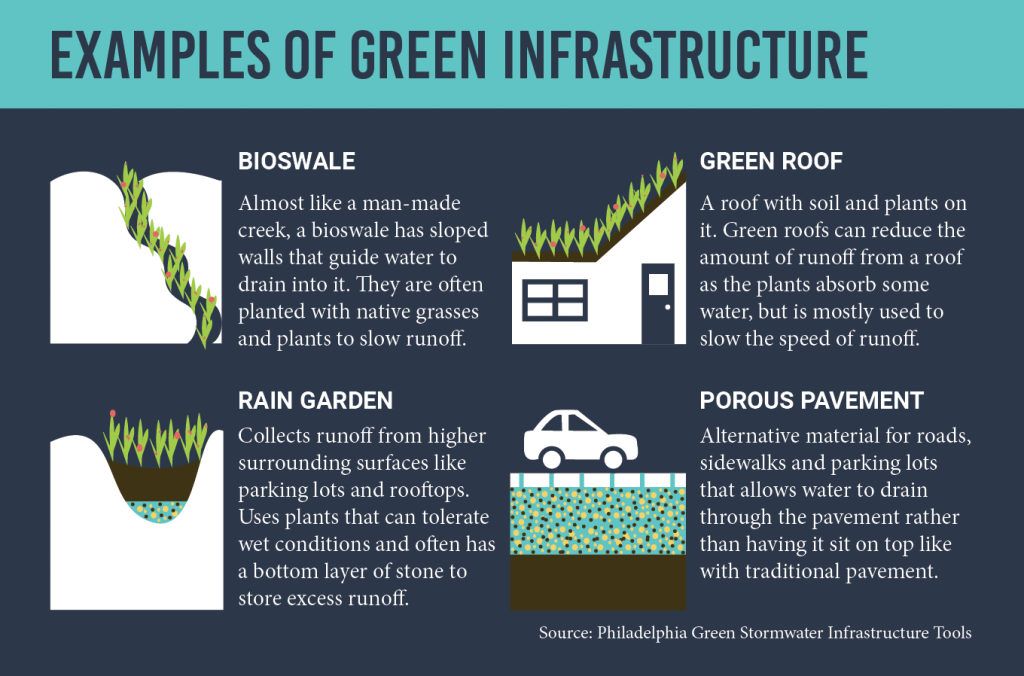

This plan is in line with the trend toward green infrastructure in major coastal cities like New Orleans and Philadelphia. Green infrastructure uses projects like rain gardens and porous pavement to store water and slow runoff as it goes into the drainage system.

The lack of detailed data for future storms can make long-term, expensive infrastructure investments seem risky. One way to build a little flexibility into a new infrastructure project is to focus on creating many green infrastructure sites rather than one big traditional project like a new tunnel or underground retention chamber.

“These approaches, like green stormwater infrastructure, that are adaptive in nature are really a priority,” said Julie Rockwell, the manager of Philadelphia Water Department’s Climate Change Adaptation Program.

In New Orleans, the ISeeChange community is working to evaluate the impact of these investments as the city turns to green infrastructure to manage stormwater.

In the months to come, Dane County officials will study the August 20 storm and work with researchers who are preparing a new Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts report. They also plan to do education outreach and want communities to be involved in preparing for the future.

“Certainly six months from now we’ll have a lot more to say,” Merritt said.

That’ll be just in time for the spring rains.

Share your observations on ISeeChange

Have storms in your area been getting more intense? Has it caused flooding? Tell us about it in an ISeeChange post. If you have a rain gauge, you can help us track rain intensity over time. If you know green infrastructure is coming to your neighborhood, you can help us measure its impacts.

And keep sharing any autumn weirdness you see, and as winter approaches be sure to document any “Firsts of Season” in your neighborhood.

Story by Samantha Harrington for ISeeChange in Partnership with Yale Climate Connections

Cover photo by Wisconsin National Guard, photo by Capt. Joe Trovato.